LE LIME E LE RASPE. UTENSILI PER SAGOMARE E RIFINIRE / FILES AND RASPS. SHAPING AND FINISHING TOOLS

English translation at the end of the article

Lime e raspe sono utensili antichi, molto utilizzati nella falegnameria amanuense. Vengono impiegati per sagomare il legno, smussare gli spigoli e creare rotondità ma anche per rifinire superfici già lavorate con altri utensili.

Seppur simili per forma e dimensioni le raspe e le lime non devono essere confuse tra di loro in quanto svolgono lavorazioni differenti. Le raspe sono caratterizzate dalla presenza di rilievi taglienti e piccoli scavi, ricavati direttamente dal metallo, che possono essere realizzati sia a macchina che a mano e che rimuovono materiale più o meno velocemente a seconda della grandezza e del numero di taglienti presenti.

Le lime invece presentano dei solchi trasversali per tutta la loro larghezza e rimuovono poco materiale per volta.

Le raspe lasciano una superficie grezza e spesso, dopo il loro utilizzo, vengono impiegati altri utensili come la pialla, la vastringa, la rasiera e le lime stesse al fine di ottenere una superficie più liscia. Le raspe sono utensili utilizzati esclusivamente nella lavorazione del legno mentre per le lime non esiste una differenziazione tra lime per legno e lime per metallo, potendo quindi utilizzare la stessa lima per ambedue i materiali. Nella pratica è comunque preferibile mantenere separate le lime che utilizziamo per il legno da quelle per il metallo.

Le lime, oltre a creare rotondità nel legno, vengono utilizzate per lavori di rifinitura, specialmente in quelle zone dove è difficile operare con altri utensili, e comunque prima di intervenire con le carte abrasive, che sono lo step finale.

LE RASPE

In falegnameria possiamo trovare raspe di pochi centimetri di lunghezza fino a 30 cm. e oltre. Un tempo le raspe venivano tutte forgiate e lavorate a mano. Oggigiorno, solo poche aziende al mondo producono raspe lavorate a mano, create da artigiani specializzati che battono il metallo con martello e punteruolo (c.d. picchettatura) creando pazientemente ogni singolo tagliente.

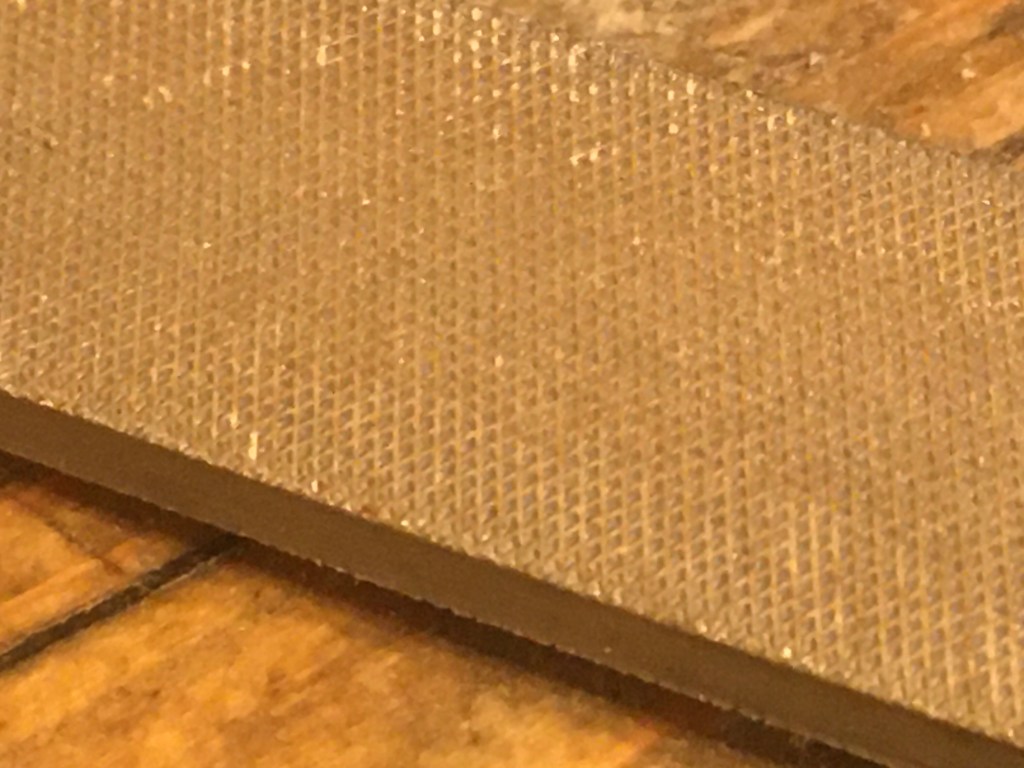

Le raspe lavorate a mano sono riconoscibili dalla dislocazione non perfettamente omogenea (seppur orientata diagonalmente) dei taglienti e da una certa loro difformità in forma e grandezza. Le raspe moderne, per contro, essendo prodotte con i macchinari, sono riconoscibili per l’ uniformità e la precisione dei taglienti.

Sul mercato del nuovo troviamo quasi tutte raspe realizzate a macchina ed è per tale motivo che quelle poche ancora realizzate a mano costano molto di più. Quest’ultime sono però di maggiore qualità e, a detta di esperti del settore, lavorano meglio di quelle realizzate a macchina.

Il grado di asportazione delle raspe viene identificato con una scala che va da 1 (maggiore aggressività) a 15 (minore aggressività). Molti produttori non riportano questa scala e identificano il grado di asportazione indicandolo con i seguenti termini inglesi: coarse (1 – 3) medium (4 – 7) fine (8 – 11) e extra fine (12 – 15).

Un esempio di raspe dalla forma classica sono la cabinet rasp e la raspa mezza tonda, molto simili nell’aspetto, che presentano un profilo rastremato verso la punta che ne facilita l’inserimento in spazi ristretti. Queste raspe hanno una faccia piatta, adatta a superfici convesse ed una faccia arrotondata adatta alle superfici concave.

Esistono anche raspe tonde (rastremate e non) utilizzate specialmente per rifinire e allargare fori, raspe piatte, raspe rifloir, combinate tonde e a forma di lancia, con lime e di svariate dimensioni. La scelta dipenderà dalle nostre esigenze, a seconda che si debbano fare lavori di scultura, di liuteria, ebanisteria, lavori di falegnameria generale, ecc.

Molti tipi di raspa presentano dei taglienti anche sui fianchi, anch’essi in grado di abradere il legno. E’ questa una particolarità utile per poter ricavare dei canali o rimuovere materiale dagli angoli.

I taglienti delle raspe sono formati in modo tale da poter lavorare in un movimento a spingere ma niente vieta di utilizzarle anche a tirare, seppure la capacità abrasiva si riduca sensibilmente e si consumino inutilmente i taglienti.

Si impugnano afferrando il manico con la mano dominante e la punta con l’altra mano. Cominciamo con passate decise, applicando molta pressione verso il basso e presentando la raspa ad un’angolazione di circa 40 gradi rispetto alla direzione di movimento. Lavoriamo sempre in favore di vena e mai contro vena, per evitare strappi. Se usiamo raspe cilindriche è buona pratica ruotare leggermente la raspa durante il movimento. Finiamo con passate sempre più leggere.

Controlliamo spesso quanto legno viene rimosso e variamo l’inclinazione, il movimento e la pressione a seconda della necessità. Dopo ogni passata, nel movimento di ritorno, è bene sollevare la raspa dal pezzo o al limite trascinarla sul pezzo ma senza fare pressione.

Utilizziamo sempre le raspe inserendo il codolo in un manico di legno. Non lasciamole mai senza manico perché, oltre ad essere scomode, potremmo farci male. Possiamo acquistare un manico già fatto oppure sagomarne uno da un blocchetto di legno.

Lavorare bene con le raspe è una pratica che si apprende con il tempo. Una volta acquisita sarà sorprendente vedere quanto materiale è stato possibile rimuovere con solo poche passate.

Le raspe sono utensili non riaffilabili ma i denti sono comunque molto resistenti in quanto sottoposti ad un procedimento di rinforzo. Se non se ne fa un uso particolarmente intensivo e se sono trattate bene, possono durare anche una vita. Per questo motivo, se pensiamo di non utilizzarle molto, è preferibile acquistarne poche, una o due al massimo, ma di buona qualità, meglio se realizzate da qualche artigiano che ancora le produce a mano. Il consiglio è di acquistare una raspa 9 o 10 (fine) e una medium o coarse, come ad esempio la Shinto rasp.

La shinto rasp è una tipologia di raspa che ricorda molto le pialle e le lime surform in quanto presentano dei fori di uscita per la segatura, attenuando così il problema dell’intasamento.

Leggendo l’ottima valutazione al riguardo fatta da Paul Sellers ho voluto acquistarne una e non posso che confermare l’ottima impressione. È risultata particolarmente aggressiva e quindi molto utile quando si desidera rimuovere molto materiale in breve tempo. Presenta un lato coarse ed un lato fine.

Nelle comuni raspe è normale che dopo poche passate le zone di fronte ai taglienti si riempiano di segatura di legno, diminuendo l’efficacia della raspa. Possiamo rimuovere tali residui utilizzando una spazzola con setole di nylon, o con setole dure (tipo quelle che si utilizzano per lavare i panni a mano), ma anche con una spazzola per le scarpe o uno spazzolino da denti. Se la segatura è particolarmente vecchia e ostinata possiamo preventivamente immergere in acqua calda e poi spazzolare, avendo l’accortezza di asciugare bene successivamente per prevenire la formazione di ruggine. Eventualmente possiamo utilizzare una spazzola con setole in metallo passandola però leggermente e sempre in diagonale (rispettando quindi la disposizione dei denti) per evitare di rovinare i taglienti.

Infine, se si prevede di non utilizzarle per parecchio tempo, proteggiamole dalla ruggine avvolgendole in una carta oliata.

LE LIME

Le lime sono più conosciute per i lavori sul metallo che non sul legno, ma possono essere impiegate utilmente anche per quest’ultimo, più che per sagomare, per rifinire superfici già precedentemente lavorate. Abbiamo già visto in un precedente post alcuni tipi di lime per metallo, quando abbiamo parlato dell’affilatura delle seghe.

La distinzione fatta per le raspe in coarse, medium, fine e extra fine vale anche per le lime, variando a seconda della grandezza dei solchi presenti sulla lima. Questi solchi sono disposti in obliquo su ambedue le facce e sono talvolta presenti anche sui lati risultando molto utili ad esempio per rifinire piccoli canali nel legno.

Il loro utilizzo è del tutto simile a quello visto precedentemente per le raspe e per la loro pulizia possiamo utilizzare, oltre ai metodi visti sopra, anche le apposite spazzole con sottili fili di acciaio.

In commercio esistono innumerevoli tipologie di lime, di svariate forme e misure. Le più comuni sono quelle di misura variabile tra i 10 cm. e i 30 cm. di lunghezza e possono presentare una sola fila di denti diagonali oppure una doppia fila intrecciata di denti per una maggiore asportazione.

Le più comuni lime sono quelle piatte (ambedue le facce piatte), quelle mezze tonde (con una faccia piatta e una tonda) e quelle tonde (che sono rotonde e utili per rifinire ed allargare i fori) ma esistono anche lime di forme particolari come le rifloir, molto utili per limare in punti difficili da raggiungere.

Se non si hanno esigenze particolari, un paio di lime ad asportazione media e fine andranno bene per la maggioranza dei lavori.

Le raspe e le lime sono utensili spesso sottovalutati ma un tempo nelle vecchie botteghe artigiane erano diffusissime. Le ritengo insostituibili per alcune tipologie di lavoro in quanto estremamente versatili e maneggevoli.

Se non si hanno particolari esigenze e per i comuni lavori di falegnameria il mio consiglio è di acquistare almeno una raspa tipo surform, come la shinto rasp, per ottenere un’asportazione aggressiva e due raspe e due lime con asportazione media e fine. Dovendo acquistarne poche, compriamole di qualità e, limitatamente alle raspe, da qualche azienda che ancora le produce a mano, come la B&B artigiana, la Liogier o la Auriou. I prezzi sono elevati, ma valgono ogni centesimo speso. Di seguito inserisco dei link per le raspe ed un link per le lime Bahco.

https://www.liogier-france.fr/rapes-piquees-main-pour-le-travail-du-bois

https://www.fine-tools.com/shintorasp.html

https://forge-de-saint-juery.com/about-us/

___________________________________________________________________________________

Files and rasps are ancient tools, widely used in woodworking by hand. They are used to shape wood, smooth edges and create roundness but also to finish surfaces already worked with other tools.

Although similar in shape and size, rasps and files must not be confused with each other as they perform different processes. The rasps are characterized by the presence of sharp reliefs and small excavations, obtained directly from the metal, which can be made either by machine or by hand and which remove material more or less quickly depending on the size and number of cutting edges present.

The files, on the other hand, have transversal grooves along their entire width and remove a little material at a time.

The rasps leave a rough surface and often, after their use, other tools are used such as the plane, the spokeshave , the scraper and the files themselves in order to obtain a smoother surface. Rasps are tools used exclusively in woodworking while for files there is no differentiation between files for wood and files for metal, so it is possible to use the same file for both materials. In practice, however, it is preferable to keep the files we use for wood separate from those for metal.

The files, in addition to creating roundness in the wood, are used for finishing works, especially in those areas where it is difficult to work with other tools, and in any case before intervening with abrasive papers, which are the final step.

THE RASPS

In woodworking we can find rasps of a few centimeters in length up to 30 cm. and beyond. At one time the rasps were all forged and worked by hand. Nowadays, only a few companies in the world produce hand-made rasps, created by skilled craftsmen who hand stitch the metal with a hammer and awl so that these rasps are recognizable by the not perfectly homogeneous, albeit diagonally oriented, dislocation of the cutting edges and by a certain differences in shape and size. Modern rasps, on the other hand, being produced with machinery, are recognizable by the uniformity and precision of the cutting edges.

On the new market we find almost all machine made rasps and it is for this reason that the few still hand made cost much more. The latter, however, are of higher quality and, according to experienced woodworkers, work better than those made by machine.

The degree of removal of the rasps is identified with a scale ranging from 1 (greater aggressiveness) to 15 (less aggressiveness). Many manufacturers do not report this scale and identify the degree of removal indicating it with the following terms: coarse (1 – 3) medium (4 – 7) fine (8 – 11) and extra fine (12 – 15).

An example of a classic-shaped rasps are the cabinet rasp and the half-round rasp, very similar in appearance, which have a tapered profile towards the tip that facilitates insertion in tiny spaces. These rasps have a flat face suitable for convex surfaces and a rounded face suitable for concave surfaces.

There are also round rasps (tapered and not) used especially for finishing and widening holes, flat rasps, rifloir rasps, combined round and spear-shaped rasps, with files and of various sizes. The choice will depend on our needs, depending on whether sculpture, lutherie, cabinet making, general carpentry work, etc. are to be done.

Many types of rasp have edges also on the sides which are also capable of abrading the wood. And this is a useful feature to be able to obtain grooves or remove material from the corners.

The cutting edges of the rasps are formed in such a way as to be able to work in a pushing movement but nothing prevents them from being used also in pulling, although the abrasive capacity is significantly reduced and the cutting edges are unnecessarily worn.

They are held by grasping the handle with the dominant hand and the tip with the other hand. Let’s start with firm strokes, applying a lot of downward pressure and presenting the rasp at an angle of approximately 40 degrees to the direction of movement. We always work in favor of the grain and never against the grain, to avoid tearing. If we use round rasps it is good practice to rotate the rasp slightly during the movement. We end up with lighter and lighter passes.

We often check how much wood is removed and vary the angle, movement and pressure as needed. After each pass, in the return movement, it is good to lift the rasp from the piece or at least drag it on the piece but without applying pressure.

We always use rasps by inserting the tang into a wooden handle. Never leave them without handles because, in addition to being uncomfortable, we could get hurt. We can buy a handle already made or shape one from a wooden block.

Working well with rasps is a practice that is learned over time. Once acquired, it will be surprising to see how much material can be removed in just a few strokes.

The rasps are non-resharpenable tools but the teeth are still very resistant as they are subjected to a reinforcement process. If they are not used particularly intensively and if they are well treated, they can last a lifetime. For this reason, if we think we do not use them a lot, it is preferable to buy a few, one or two at most, but of good quality, better if made by some craftsman who still produces them by hand. The advice is to buy a 9 or 10 rasp (fine) and a medium or coarse , such as Shinto rasp .

The shinto rasp is a type of rasp that is very reminiscent of planes and surform files as they have exit holes for the sawdust, thus alleviating the problem of clogging.

Reading the excellent evaluation made by Paul Sellers in this regard, I wanted to buy one and I can only confirm the excellent impression. It was found to be particularly aggressive and therefore very useful when you want to remove a lot of material in a short time. It has a coarse side and a fine side. In common rasps it is normal that after a few passes the areas in front of the cutting edges are clogged with wood sawdust, decreasing the effectiveness of the rasp. We can remove these residues using a brush with nylon bristles, or with hard bristles (such as those used to wash clothes by hand), but also with a shoe brush or a toothbrush. If the sawdust is particularly old and stubborn, we can first immerse it in hot water and then brush, taking care to dry it well afterwards to prevent the formation of rust. If necessary, we can use a brush with metal bristles, however, passing it slightly and always diagonally (thus respecting the arrangement of the teeth) to avoid damaging the cutting edges.

Finally, if you plan not to use them for a long time, let’s protect them from rust by wrapping them in oiled paper.

THE FILES

Files are better known for working on metal than on wood, but they can also be usefully used for the latter, rather than for shaping, to finish previously worked surfaces. We have already seen in a previous post some types of files for metal, when we talked about sharpening saws.

The distinction made for coarse , medium, fine and extra fine rasps also applies to files, varying according to the size of the grooves present on the file. These grooves are arranged obliquely on both faces and are sometimes also present on the sides, making them very useful, for example, for finishing small grooves in the wood.

Their use is very similar to that seen previously for the rasps and for their cleaning we can use, in addition to the methods seen above, also the special brushes with thin steel wires.

On the market there are countless types of files, of various shapes and sizes. The most common are those of variable size between 10 cm. and 30 cm. in length and may have a single row of diagonal teeth or a double intertwined row of teeth for greater removal.

The most common files are the flat ones (both flat faces), the half round ones (with a flat and a round face) and the round ones (which are round and useful for finishing and widening the holes) but there are also files of particular shapes such as the rifloirs, very useful for filing in hard to reach places.

If you don’t have any special needs, a couple of medium and fine files will work for most jobs.

Rasps and files are often underestimated tools but once they were very widespread in the old artisan shops. I consider them irreplaceable for some types of work as they are extremely versatile and easy to handle.

If you do not have particular needs and for common woodworking, my advice is to buy at least one surform type rasp, such as the shinto rasp for aggressive removal and two rasps and two files with medium and fine removal. Having to buy a few, let’s buy them of quality and, limited to the rasps, from some company that still produces them by hand, such as the artisan B&B, the Liogier or the Auriou. The prices are high, but they are worth every penny. Above I have included links for rasps and a link for Bahco files .

Lascia un commento