PIALLE SPECIALI. PIALLE PER BATTUTE. STANLEY N. 90 E STANLEY N. 93 / SPECIAL PLANES. REBATE OR RABBET PLANES. STANLEY N. 90 AND STANLEY N. 93 PLANES

English translation at the end of the article

Qualche mese fa ho parlato di un particolare modello di pialla, la Stanley n. 78. Quel tipo di pialla rientra tra le cosiddette rebate o rabbet planes (pialle per battute), la cui principale funzione è giustappunto quella di praticare battute nel legno. Per un approfondimento sulla Stanley n. 78 e le pialle per battute in generale vi rimando al link di seguito. Pialle particolari. Pialle per battute. Pialla Stanley n. 78.

Come accennavo in quell’articolo, nel panorama delle pialle per battute esistono svariati modelli dedicati a specifiche lavorazioni. Ne farò un breve riepilogo a fine articolo. Adesso

mi interessava approfondire la conoscenza di due particolari modelli di pialle per battute: la Stanley n. 93 (comunemente denominata shoulder plane) e la Stanley n. 90 (detta anche bullnose plane).

Sono ambedue pialle in metallo rifinite in nickel e si differenziano sensibilmente, per caratteristiche e funzionamento, dalle normali sponderuole in legno (di cui parlerò in un futuro articolo). Ambedue rientrano nella categoria delle sponderuole (che a loro volta rientrano nella categoria delle rebate plane o rabbet plane o pialle per battute) e, sebbene sia la Stanley n. 93 che la Stanley n. 90, siano chiamate anche shoulder plane (pialle adatte a lavorare le spalle dei tenoni) nel linguaggio legnofilo si è soliti riferirsi alla n. 93 come ad una shoulder plane mentre alla n. 90 come ad una bullnose plane (pialla a naso di toro). Premesso che considero tutte queste classificazioni di poco interesse, mi rendo comunque conto che, anche volendo approfondire le varie classificazioni, non sia facile districarsi fra le varie nomenclature. E in tal senso anche i termini inglesi non aiutano.

Prima di entrare nello specifico volevo soffermarmi brevemente su alcune caratteristiche comuni ai due modelli Stanley e fare qualche considerazione a carattere generale. Come abbiamo visto, la caratteristica principale della Stanley n. 78 è quella di creare battute nel legno e le sponderuole in legno svolgono sostanzialmente la stessa funzione. Le Stanley n. 90 e n. 93 invece, seppure siamo potenzialmente in grado di effettuare lo stesso lavoro (prevedendo però alcune accortezze), di solito vengono impiegate per compiti meno gravosi e di rifinitura intervenendo solo in un secondo momento su un lavoro già effettuato, come ad esempio nel caso della rifinitura delle spalle dei tenoni nell’incastro a tenone e mortasa, delle battute nell’incastro dente e canale e in tutte quelle circostanze in cui sia necessario ottenere l’ortogonalità di due superfici contigue. Questi tipi di pialla non sono dotati di battute parallele, guide laterali e stop di profondità (esistono comunque altri modelli di pialle per battute che ne sono provvisti, uno su tutti la moving fillister).

Sono particolarmente solide, di forma compatta e quindi maneggevoli e pratiche, potendo essere impiegate anche con una sola mano. Presentano un basso angolo di seduta (low angle), lavorano con il bisello della lama rivolto verso l’alto (bevel up) ed essendo la lama esposta sui due lati del corpo pialla possono essere utilizzate in entrambi i sensi di lavorazione, a differenza delle comuni pialle (anche quelle con battuta).

Il fatto che la larghezza della lama sia di qualche decimo di millimetro maggiore rispetto alla larghezza della suola non è un difetto di fabbricazione ma del tutto normale e funzionale alla perfetta adesione del tagliente alla battuta. Il basso angolo di taglio (12 gradi di seduta più 25 di affilatura del tagliente) le rende infine particolarmente efficaci nelle lavorazioni sulla testa del legno ovviando quindi al problema dello strappo delle fibre. Proprio la mancanza di guide e battute ne limita però l’utilizzo e le relega, come accennato sopra, a lavori di ritocco su battute già realizzate con altri utensili (come sponderuole ed incorsatoi). Non le reputo perciò pialle fondamentali (come lo sono ad esempio le pialle da finitura, le c.d. smoothing planes) e potremmo quindi valutarne l’acquisto in un secondo momento anche se, in alcune situazioni, possono rivelarsi utili. Vediamole adesso singolarmente più nello specifico.

Stanley 93

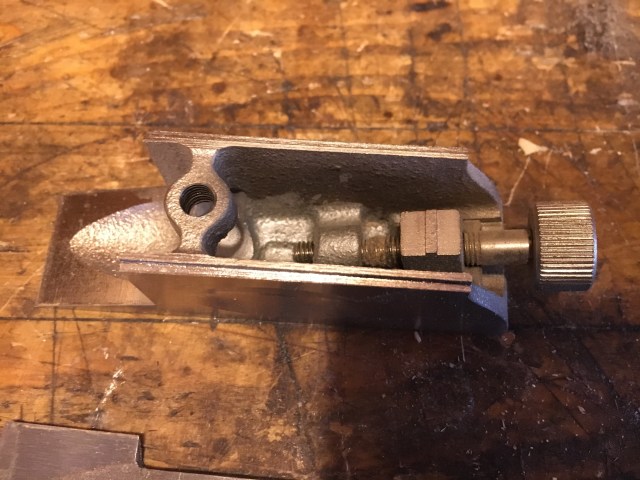

Detta anche shoulder plane (lett. pialla per spalla), perché particolarmente adatta a lavorare le spalle degli incastri dei tenoni (ma non solo), è del tutto simile alla Stanley n. 90 eccetto che per le dimensioni. È più grande, più pesante e più lunga della n. 90. È composta di due corpi in ghisa tenuti assieme per mezzo di una vite centrale.

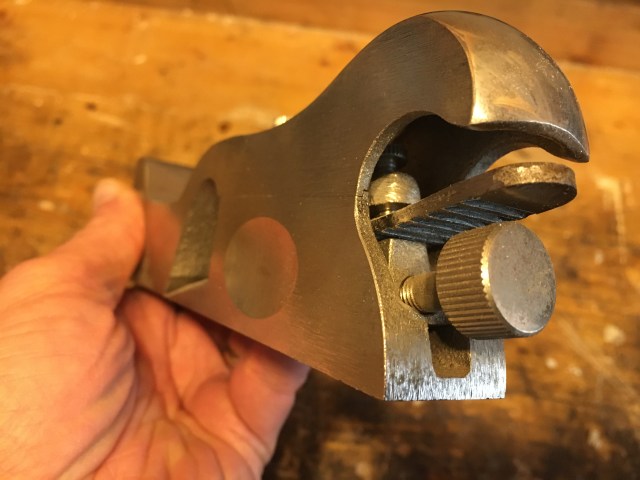

Agendo sulla vite centrale più grande è possibile rimuovere la parte superiore (assimilabile al cap iron delle normali pialle da banco) ed utilizzare la pialla nella cosiddetta versione chisel plane o flush plane (pialla a raso).

Senza il frontale riesce ad arrivare in punti altrimenti non raggiungibili a causa dell’ingombro della parte antistante la lama. Si rivela utile se si deve ad esempio portare a livello una spina di legno o rimuovere dagli angoli interni i residui di colla.

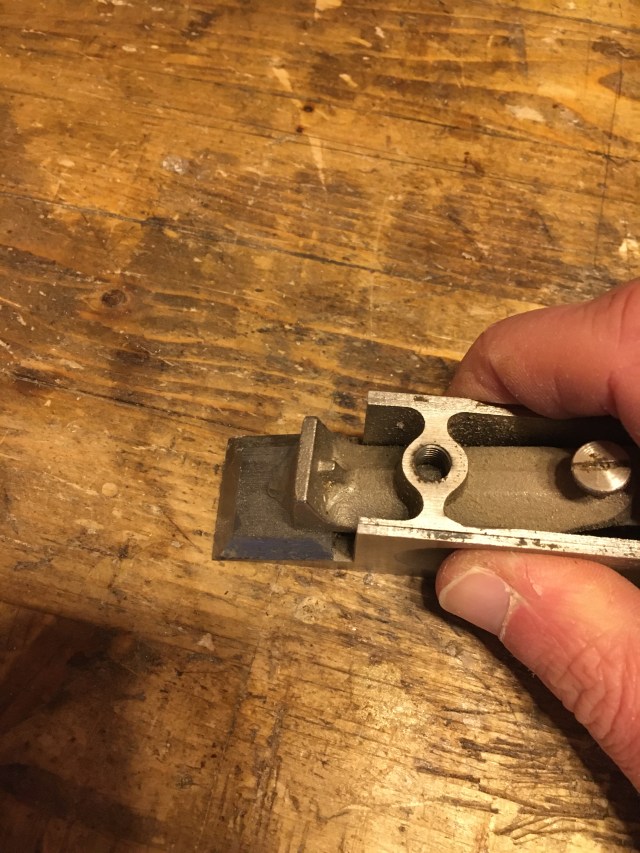

Svitando l’altra vite (consentito solo se è stata preventivamente rimossa la vite centrale) è possibile rimuovere il controferro, estraendolo dalla parte anteriore. Sempre dalla parte anteriore è possibile sfilare anche la lama. Quest’ultima operazione può risultare leggermente complessa a causa delle scanalature presenti sulla lama che ne permettono l’inserimento nell’apposito rilievo.

La lama può essere spostata avanti e indietro per mezzo della rotella posteriore ma, essendo la corsa della rotella abbastanza breve, è importante inserire la lama nella scanalatura che più permetta al tagliente di trovarsi già leggermente fuori dalla bocca della pialla.

Un’altra accortezza, nel rimontare la lama inserendola dal fronte, è quella di tenerla il più possibile dritta rispetto alla bocca e questo specialmente quando si sta avvitando il controferro. Inoltre non bisogna serrare troppo la vite che tiene insieme lama e controferro altrimenti non sarà più possibile agire sulla rotella che comanda il movimento avanti – indietro della lama.

Il corpo della pialla presenta due sagomature sui fianchi che ne facilitano l’impugnatura. È possibile utilizzarla ad una o due mani e sia in posizione dritta sulla sua base che reclinata su un fianco a seconda del tipo di lavorazione. Essendo aperta su ambedue i fianchi può inoltre lavorare in ambedue le direzioni rispetto al pezzo. Come detto sopra, il fatto che la lama fuoriesca rispetto ai fianchi di pochi decimi di millimetro è normale. Anzi in fase di affilatura del tagliente è importante non andare ad alterare questa larghezza se non vogliamo penalizzare la perfetta funzionalità della pialla.

Stanley n. 90

Detta anche bullnose plane (lett. pialla a naso di toro) per la sua particolare forma, è del tutto simile nel funzionamento alla Stanley n. 93. La differenza è solo nella forma e nelle dimensioni più contenute che la rende di fatto la sorella minore. Essendo più piccola può essere utilizzata con una sola mano e la parte antistante la lama, di dimensioni ridotte, ne permette l’utilizzo in ambiti più ristretti senza però rinunciare alla stabilità garantita dal seppur ridotto frontale.

La struttura ed i settaggi sono del tutto similari a quelli della Stanley n. 93 descritta sopra. Anche per questa bullnose plane è possibile separare la parte superiore del corpo inferiore utilizzandola come una flush o chisel plane.

L’affilatura del tagliente non necessita di particolari accortezze. L’unico accorgimento è quello di non perdere mai quel rapporto di perpendicolarità tra il filo del tagliente e il fianco della lama stesso per non andare ad inficiare la precisione della pialla quando andrà a rifinire le pareti delle battute. Come per quasi tutte le pialle il tagliente va impostato a 25 gradi. Trattandosi di pialle che lavorano bevel up (bisello rivolto verso l’alto) l’angolo di seduta di questi modelli è di 12 gradi, ottenendo quindi un angolo complessivo di 37 gradi.

Le sponderuole in legno, come vedremo, hanno invece un angolo di seduta di circa 50 gradi e la lama, per motivi di stabilità propri delle pialle in legno, lavora in modalità bevel down (bisello rivolto verso il basso). Il modello in foto monta la lama inclinata per meglio lavorare traverso vena e avere una migliore aderenza alla battuta. Il miglior modo di piallare con le Stanley n. 90 e n. 93 è quello di lavorare esponendo poca lama e asportando poco materiale per volta. Allentando la grande vite centrale che tiene insieme le due parti che compongono la pialla è comunque possibile far slittare la parte superiore su quella inferiore di fatto aumentando o diminuendo l’apertura della bocca. Una volta trovata la giusta posizione si provvederà di nuovo a bloccare le due parti per mezzo della vite. Su queste pialle non è previsto alcun sistema di aggiustamento laterale della lama. Dovendo effettuare un lavoro di finitura sono costruite con estrema cura, rifinite e ben settate. Per la rettifica di battute con superfici ortogonali è molto importante che i fianchi e la suola siano perfettamente a 90 gradi tra di loro così come la lama deve essere parallela ai fianchi ed il tagliente della lama parallelo alla bocca della suola e perpendicolare con i fianchi stessi. Personalmente le ho trovate molto utili anche per eliminare l’inestetismo della battuta a gradini che può accadere quando le passate con la sponderuola tendono a sovrapporsi a causa di una non perfetta aderenza in battuta. Solitamente i nuovi modelli escono di fabbrica perfettamente tarati, necessitando quindi di pochi accorgimenti. La nostra attenzione dovrà più che altro concentrarsi sulla corretta affilatura del tagliente e l’esatto posizionamento della lama. Sulle pialle usate, come quelle comprate su Ebay, invece dovremo fare un po’ più di attenzione e verificarne tutte le simmetrie, come detto sopra. Su questi modelli, in fase di acquisto, cerchiamo di indagare bene le foto ed evitare quelle che riportano disallineamenti tra la parte superiore ed inferiore della pialla, che mostrano chiare ammaccature sul corpo e fessurazioni sotto la suola o vicino alla bocca.

In passato si sono costruiti molti modelli di pialle per battute ognuna con peculiarità che le distinguevano dalle altre. I principali costruttori erano Stanley, Record. Solo per citarne qualcuno, tra i modelli storici di maggior successo possiamo ricordare, oltre alle predette n.90 e n.93, le Stanley n.92 e n.94 e le Record n. 311, n. 041 e n. 076. Tra i modelli di nuova produzione ho letto recensioni positive per la Luban 92, la Clifton 410 e la Rider 311 (tutte che ricordano nella forma le storiche Record). In particolare, la Rider 311 riprende il famoso modello Record n. 311 che si distingueva per la possibilità di sostituire il frontale diventando di fatto una bullnose plane o di rimuoverlo trasformandosi in una chisel plane. Mi ripropongo di concludere la panoramica sulle pialle per battute parlando delle sponderuole in legno che, per le loro caratteristiche e funzionamento, meritano un articolo dedicato.

______________________________________________________________

A few months ago I talked about a particular model of plane, the Stanley n. 78. That type of plane falls within the so-called rebate or rabbet planes , whose main function is that of making rebates in wood. For more information on Stanley n. 78 and the rebate planes in general I refer you to the link below. Special planes. Rabbet planers. Stanley No. 78. As I mentioned in that article, in the panorama of rabbet planes there are various models dedicated to specific processes. I will make a brief summary at the end of the article. Now I was interested in learning more about two particular models of rebate planes: the Stanley no. 93 (commonly referred to as shoulder plane ) and Stanley No. 90 (also called bullnose plane ). They are both metal planes finished in nickel and differ significantly, in terms of characteristics and functioning, from the normal wooden rebate planes (which I will talk about in a future article). Both fall into the category of shoulder planes (which in turn fall into the category rebate plane or rabbet plane) and although the Stanley n. 93 and Stanley No. 90, are also called shoulder planes (planes suitable for working the shoulders of tenons) in the woodworking language it is usual to refer to n. 93 as to a shoulder plane while at n. 90 such a bullnose plane. Given that I consider all these classifications of little interest, I still realize that, even if I want to deepen the various classifications, it is not easy to disentangle the various nomenclatures. And in that sense even the English terms don’t help. Before going into the specifics, I wanted to briefly focus on some characteristics common to the two Stanley models and make some general considerations. As we have seen, the main feature of the Stanley No. 78 is to create rebates and the wooden rebate planes essentially perform the same function. The Stanley no. 90 and n. 93 on the other hand, although they are potentially able to carry out the same work (but providing some precautions), they are usually used for less demanding and finishing tasks, intervening only later on a work already carried out, such as in the case of finishing of the shoulders of the tenons in the tenon and mortise joint, of the joints in dado joints and in all those circumstances in which it is necessary to obtain the orthogonality of two contiguous surfaces. These types of planes are not equipped with parallel fence, lateral guides and depth stops (however, there are other models of planes that are equipped with them, one above all the moving fillister ). They are particularly solid, compact in shape and therefore easy to handle and practical, as they can also be used with one hand. They are low angle, so they work with the blade bevel up and being the blade exposed on both sides of the plane body, they can be used in both directions of processing, unlike the common planes (even those with stop). The fact that the width of the blade is a few tenths of a millimeter greater than the width of the sole is not a manufacturing defect but completely normal and functional to the perfect adhesion of the cutting edge to the rebate. The low cutting angle (12 degrees of sitting plus 25 of sharpening of the cutting edge) makes them particularly effective in working on the end grain, thus obviating the problem of tear out of the fibers. Precisely the lack of guides and stops however limits their use and relegates them, as mentioned above, for refining works on rebates already made with other tools (such as grooving planes and rebate planes). I do not do count so fundamental planes (as are, for example, the smoothing planes ) and we can then evaluate the purchase at a later time even if, in some situations, may be useful. Let’s see them now individually in more specific terms.

Stanley 93

Also known as shoulder plane , because it is particularly suitable for working the shoulders of tenon joints (but not only), it is very similar to Stanley n. 90 except for the size. It is larger, heavier and longer than No. 90. It is made up of two cast iron bodies held together by a central screw. By acting on the larger central screw it is possible to remove the upper part (similar to the cap iron of normal bench planes) and use the plane in the so-called chisel plane or flush plane version . Without the front, it can reach points otherwise not reachable due to the nose of the plane. It is useful if, for example, you need to level a wooden pin or remove glue residues from the internal corners. By unscrewing the other screw (only possible if you have unscrewed the other larger central screw) it is possible to remove the iron , extracting it from the front. The blade can also be removed from the front. This last operation can be slightly complex due to the grooves on the blade that allow it to be inserted into the appropriate nip. The blade can be moved back and forth by means of the rear wheel but, since the stroke of the wheel is quite short, it is important to insert the blade in the groove that best allows the cutting edge to be already slightly out of the plane mouth. Another precaution, in reassembling the blade by inserting it from the front, is to keep it as straight as possible with respect to the mouth and this especially when you are screwing the iron . Furthermore, the screw that holds the blade and iron together must not be tightened too much otherwise it will no longer be possible to act on the wheel that controls the forward – backward movement of the blade. The body of the plane has two shapes on the sides that make it easier to handle. It can be used with one or two hands and either in a straight position on its base or reclined on its side depending on the type of working. Being open on both the sides can also work in both directions relative to the workpiece. As mentioned above, the fact that the blade protrudes from the sides by a few tenths of a millimeter is normal. Indeed, when sharpening the cutting edge it is important not to alter this width if we do not want to affect the perfect functionality of the plane.

Stanley No. 90

Also called bullnose plane due to its particular shape, it is completely similar in working to Stanley n. 93. The difference is only in the shape and in the smaller dimensions that makes it the younger sister. Being smaller, it can be used with one hand only and the part in front of the blade, of reduced dimensions, allows it to be used in more restricted areas without sacrificing the stability guaranteed by the even reduced front. The structure and settings are very similar to those of the Stanley n. 93 described above. Also for this bullnose plane it is possible to separate the upper part of the lower body using it as a flush or chisel plane .

The sharpening of the cutting edge does not require special precautions. The only precaution is to never lose that perpendicular relationship between the edge of the cutting edge and the side of the blade itself so as not to affect the precision of the plane when it will finish the rebates. As with most planes, the cutting edge should be set at 25 degrees. By treating planes that work bevel up the seat angle of these models is 12 degrees, thus obtaining an overall angle of 37 degrees. The wooden rebate planes, as we will see, instead have a seat angle of about 50 degrees and the blade, for reasons of stability typical of wooden planes, works in bevel down mode. The model in the photo has the inclined blade to better work across the grain and have a better adherence to the rebate. The best way to plane with the Stanley n. 90 and n. 93 is to work by exposing a few blade and removing a little material at a time. By loosening the large central screw that holds the two parts that keeps the plane together, it is still possible to slide the upper part over the lower one, effectively increasing or decreasing the opening of the mouth. Once the right position has been found, the two parts will be locked again by means of the screw. There is no lateral blade adjustment system on these planes. Having to carry out a finishing work, they are built with extreme care, finished and well set. For the rebate finishing with orthogonal surfaces it is very important that the sides and the sole are perfectly 90 degrees to each other as well as the blade must be parallel to the sides and the cutting edge of the blade parallel to the mouth of the sole and perpendicular to the sides themselves . Personally, I have also found them very useful for correcting the imperfection of the stepped rebate that can occur when the passes with the rebate plane tend to overlap due to a non-perfect adherence on the rebate. Usually the new models leave the factory perfectly calibrated, therefore requiring a few adjustments. Our attention should mainly focus on the correct sharpening of the cutting edge and the exact positioning of the blade. On the used planes, such as the ones bought on Ebay, instead we will have to pay a little more attention and check all the symmetries, as mentioned above. If we purchase on Ebay pay also attention that the upper and lower part are not misaligned, that the are no crcaks in the body plane or into the sole and near the mouth. In the past, many rebate plane models have been built, each with peculiarities that distinguished them from the others. The main builders were Stanley, Record. Just to name a few, among the most successful historical models we can mention, in addition to the aforementioned n.90 and n.93, the Stanley n.92 and n.94 and the Record n. 311, n. 041 and n. 076. Among the new production models I have read positive reviews for the Luban 92, the Clifton 410 and the Rider 311 (all reminiscent of the historic Records in shape). In particular, the Rider 311 takes up the famous Record model no. 311 which was distinguished by the possibility of replacing the front panel becoming a bullnose plane or of removing it by transforming it into a chisel plane. I intend to conclude the overview of the rebate planes by talking about the wooden rebate planes which, due to their characteristics and functioning, deserve a dedicated article.

______________________________________________________________

Lascia un commento