IL LEGNO E LA SUA LAVORAZIONE MANUALE. I MOVIMENTI DEL LEGNO / WOOD AND WOODWORKING BY HAND. WOOD MOVEMENTS

English translation at the end of the article

I movimenti del legno sono dovuti in larghissima parte all’umidità in esso contenuta. La trattazione dell’argomento sarebbe estremamente vasta ma in questo post vorrei parlare solo a grandi linee di alcuni aspetti legati al tema, quantomeno quelli che hanno maggiori implicazioni con la lavorazione manuale del legno. Per alcuni

approfondimenti rimando comunque al seguente link Il legno e la sua lavorazione manuale. La trasformazione del legno: dall’ albero al legname / Wood and woodworking by hand. Transformation of wood: from trees to wood

A differenza di materiali come la plastica o il metallo, che sono caratterizzati da una struttura omogenea, il legno presenta una spiccata eterogeneità. Non solo tra specie diverse ma anche all’interno della specie e della pianta stessa. Questa estrema differenziazione rende ancora più difficoltoso il lavoro del falegname che non potrà raffidarsi ad una conoscenza generica del legno ma dovrà, posta la tavola sul banco e prima di iniziare il lavoro, valutare attentamente molti fattori come la forma, l’andamento della venatura, i nodi, la durezza, l’umidità ecc. In effetti tutta una serie di elementi esterni influiscono, in maniera più o meno determinante, sulla eterogeneità appena citata come ad esempio la provenienza della pianta, l’esposizione alla luce e agli agenti atmosferici, le variazioni climatiche ed ambientali, la tecnica di abbattimento e di segagione, il metodo di stagionatura adottato ecc.

L’estrema variabilità dell’essenza legno si riflette in continui movimenti ed in una estrema instabilità. Non è difficile infatti notare come il legno abbia continue interazioni con gli elementi primordiali della natura: il fuoco (sotto forma di luce e calore), l’aria e l’acqua. È facile altresì osservare questa relazione tra tali elementi e gli alberi. Quello che invece è meno evidente è riuscire a verificare quanto questa interazione prosegua anche dopo l’abbattimento dell’albero e persino nel manufatto ultimato. Quante volte ci è capitato infatti di vedere fessurazioni nel piano di un tavolo o un mobile che balla a causa del ritiro di una gamba o gli incastri allentati dei cassetti che non chiudono più bene. Ebbene tutti questi effetti sono dovuti alla stessa causa: la perdita di umidità del legno. Le piante, così come il corpo umano, sono composte da una grossa percentuale di acqua e questa acqua viene persa in modo più o meno naturale. In un precedente post di questa serie si era detto che, non appena effettuato l’abbattimento dell’albero, dal taglio fuoriesce spontaneamente acqua dagli strati esterni e questa richiama a sua volta altra acqua proveniente dalle zone più interne della pianta. Questo processo di svuotamento avviene naturalmente e senza sostanziale ritiro del legno (causando unicamente un calo di peso) e si arresta quando l’umidità arriva al cosiddetto “punto di saturazione” delle fibre. Da questo momento in poi il legno potrà perdere altra umidità mediante la stagionatura naturale e successivamente attraverso la pratica dell’essiccazione artificiale. È solo in queste due ultime fasi che il legno comincia a ritirarsi ed a deformarsi denotando quei difetti di imbarcamento, svergolatura, ritiro e fessurazione di cui parleremo in questo capitolo.

L’intervallo di umidità che va dal punto di saturazione delle fibre all’umidità zero è detto campo igroscopico. In questo periodo di tempo il legno interagisce continuamente con l’aria dando origine ai fenomeni detti di adsorbimento (il legno assorbe umidità dall’aria circostante) e di desorbimento (il legno rilascia acqua nell’aria sotto forma di vapore acqueo). In teoria se i due fenomeni andassero di pari passo il legno non subirebbe alcun mutamento. Nella realtà sono processi che differiscono considerevolmente tra loro cosicché nel legno potremo notare rigonfiamenti dovuti all’assorbimento dell’acqua e fessurazioni, ritiri e imbarcamenti dovuti al desorbimento della stessa. Volendo riepilogare a grandi linee le varie tappe della discesa dell’umidità in un legno in essiccazione potremmo dire che il legno appena abbattuto detiene una percentuale di umidità di circa il 60%. Tale umidità decresce naturalmente dopo il taglio fino ad arrivare a valori oscillanti tra il 28% e il 40% (punto di saturazione delle fibre, convenzionalmente fissato al 30%). Per far scendere ancora l’umidità si interviene con i processi di stagionatura. Dapprima con la stagionatura naturale si riesce a scendere ad una umidità di circa il 22% (a tale percentuale il legno è detto “fresco”) per poi calare ancora, sino a circa il 16%. Di seguito si interviene con l’essiccazione artificiale che può portare l’umidità anche fino allo 0%.

Il contenuto di umidità del legno è espresso come rapporto percentuale tra il peso dell’acqua contenuta nel legno e il peso del legno anidro (ovvero senz’acqua). Esistono principalmente due metodi di misurazione: quello gravimetrico e quello elettrico. Il metodo gravimetrico è il metodo classico che implica una doppia pesata: si pesa un frammento di legno non stagionato, successivamente lo si asciuga in un forno e poi lo si ripesa di nuovo. Si sottrae quindi il peso del pezzo asciutto a quello del pezzo umido, si divide per il peso del pezzo asciutto e lo si moltiplica per cento. Oggigiorno questo metodo è stato ampiamente rimpiazzato da quello elettrico, più comodo e veloce, praticato mediante l’ausilio di igrometri specifici per il legno con funzionamento a resistenza o dialettrico.

Se si provasse a lavorare un legname non ancora assestatosi con l’umidità circostante otterremmo tavole di forme diverse da quelle desiderate. Il fenomeno del ritiro, così come quello della dilatazione e del rigonfiamento non è omogeneo su tutto il legno, variando sensibilmente a seconda che si consideri la direzione radiale, tangenziale o assiale. Inoltre il ritiro o la dilatazione del legno differiscono notevolmente anche a seconda che si tratti di legni dolci o di legni duri. Il fenomeno del ritiro e del rigonfiamento è comunque maggiormente riscontrabile nel legno massello rispetto alle altre tipologie di legno. I movimenti in direzione longitudinale (o assiale) del legno sono molto ridotti. Il movimento del legno è invece particolarmente accentuato nella direzione tangenziale e radiale. I movimenti del legno, dovuti alla perdita di umidità, causano il ritiro del legno e di conseguenza non solo la variazione delle dimensioni della tavola ma anche della forma stessa. Per dare un’idea dell’entità del fenomeno, un manufatto realizzato in ciliegio massello con un piano di circa 90 cm. di lunghezza posto in un laboratorio con umidità al 75%, una volta trasferito in una abitazione con umidità al 50% si restringerà di circa 1 cm.

Prima di passare in rassegna le varie tipologie di mutamento della forma del legno è interessante considerare una semplice ma essenziale regola pratica. Osservando una tavola di testa si potranno vedere gli anelli di accrescimento. Gli anelli del legno si aprono man mano che il legno si asciuga assecondando la loro naturale tendenza a raddrizzarsi. Da questa regola ne deriva che una tavola con taglio tangenziale tenderà a deformarsi più di una tavola con taglio radiale. In particolare, una tavola sezionata con taglio tangenziale subirà un ritiro soprattutto longitudinale, dovuto alla maggiore forza di trazione degli anelli, mentre una tavola sezionata con taglio radiale subirà poco ritiro nel senso della larghezza e quasi nullo nel senso dello spessore. Generalmente si osserva che gli anelli esterni, più lunghi, si ritirano maggiormente degli anelli interni. È per questo motivo che le tavole tendono a curvarsi trasversalmente o ad imbarcarsi nel senso della loro larghezza soprattutto nelle tavole segate con taglio tangenziale.

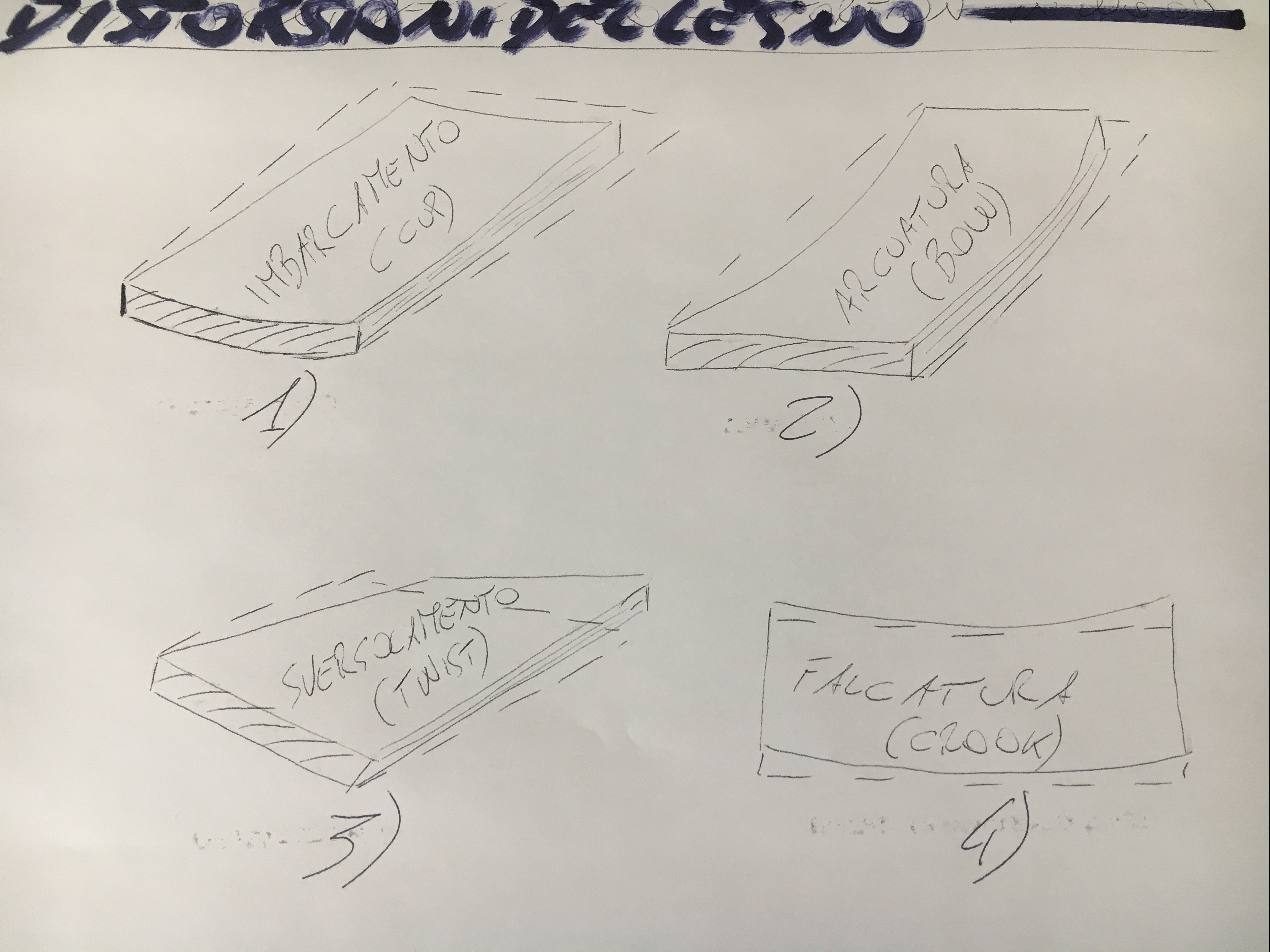

Per imbarcamento (o imbarcatura) nel linguaggio comune si intende qualsiasi deformazione della tavola di legno. Si possono ricomprendere in tale fenomeno, l’imbarcatura propriamente detta, la svergolatura ed il ritiro. Nel fenomeno dell’imbarcatura si è soliti distinguere tra imbarcatura trasversale, in cui la tavola si curva all’indietro nel senso della larghezza e imbarcatura longitudinale, in cui la tavola si curva ad arco nel senso della lunghezza. A sua volta nell’imbarcatura longitudinale si distingue tra falcatura (il nome deriva dalla caratteristica forma di falce che assume la tavola) e arcuatura, a seconda che il legno di reazione sia presente rispettivamente sul bordo della tavola o nella zona centrale della stessa. Nel fenomeno della svergolatura si distingue tra la svergolatura semplice, in cui la tavola rimane piatta ma tende a curvarsi ai bordi e la svergolatura concava in cui la tavola appare contorta e dalla caratteristica forma elicoidale. Infine abbiamo il fenomeno del ritiro per cui un materiale a sezione quadra assume una forma rettangolare ed un materiale a sezione tonda assume una forma ovale (nel gergo si dice che tende a “diamantarsi”).

In presenza di tutti questi difetti talvolta si fa uso del vapore acqueo per restituire umidità al legno e cercare così di “stirare” le fibre, restituendogli una forma accettabile che poi andrà ulteriormente corretta, sempre se non troppo compromessa, con gli idonei utensili manuali. Una perdita di umidità troppo repentina, oltre ad essere causa delle problematiche di cui sopra, può generare anche spaccature interne, superficiali e fessurazioni. Le spaccature interne si creano quando il legno esterno della tavola asciuga più velocemente di quello interno. Le spaccature superficiali generalmente si manifestano lungo i raggi midollari e sono provocate da un’essiccazione troppo veloce della superficie del legno. Le fessurazioni, infine, (ma anche le le spaccature) hanno origine generalmente vicino al legno di testa dove il fenomeno del ritiro è maggiore.

Quanto detto fino ad adesso ha dei risvolti di particolare importanza ai fini del lavoro del falegname. L’ambiente dove si svolge l’attività lavorativa dovrebbe possedere caratteristiche di luminosità e basso tasso di umidità in relazione all’ambiente esterno, essere fresco e sufficientemente ventilato. Queste particolari condizioni creano un microclima adeguato a limitare i movimenti del legno dovuti all’acclimatazione con l’ambiente circostante e garantiscono allo stesso tempo un certo grado di salubrità. Non di rado può accadere invece, specialmente tra gli hobbisti, che la lavorazione del legno sia effettuata in scantinati e garage con troppa umidità, poca luce e pochissima aerazione creando quindi una situazione climatica non ottimale.

Una volta trasportato dalla segheria al laboratorio taluni accorgimenti di natura pratica si rendono necessari per la corretta acclimatazione del legno. In primo luogo bisognerebbe evitare un contatto diretto tra lo stesso ed i muri esterni, le pareti dove passano i tubi dell’acqua ed i pavimenti in quanto tutte possibili fonti di umidità. In secondo luogo il legno andrebbe disposto orizzontalmente e sistemato con l’intercalare di distanziatori che permettano sia il ricircolo dell’aria tra una tavola e l’altra che il loro mantenimento in piano. Queste semplici indicazioni permetteranno di minimizzare i movimenti del legno e facilitare il raggiungimento di un’umidità equilibrata con l’ambiente in cui si trova (che in ogni caso necessiterà di un periodo di tempo variabile da qualche settimana a qualche mese).

Nella successiva fase di lavorazione il falegname dovrà effettuare la sezionatura dei pezzi avendo sempre l’accortezza di non tagliare mai il materiale alla misura finale ma di lasciare sempre dei margini, (come accade sovente ad esempio nella pratica degli incastri) così da permettere al legno di ritirarsi o di espandersi negli incastri e a seconda del luogo dove andrà sistemato il manufatto finale. Se deve effettuare l’incollaggio di tavole di costa il falegname dovrà stabilire se è più importante la stabilità finale del manufatto o la sua bellezza esteriore. Se la stabilità è un’esigenza prioritaria allora dovrà procedere alla disposizione alternata delle tavole con gli anelli di crescita accostati in direzione opposta oppure con la venatura delle tavole affiancate che risultino disposte perpendicolarmente di modo che i movimenti del legno si contrastino tra loro. Se l’aspetto estetico è più importante allora dovrà ripensare l’accostamento delle tavole così da porle con gli anelli di crescita tutti nello stesso senso e possibilmente vincolandole in una struttura che ne contenga l’imbarcamento.

Altro fattore da tenere in considerazione nella realizzazione di qualsiasi opera è conoscere la destinazione finale del manufatto così da poter tenere conto del grado di umidità dell’ambiente dove andrà collocato e scegliere di conseguenza il tipo di legname più adatto. Non esistono differenze rilevanti di umidità solo tra ambienti interni ed esterni ma anche a seconda del tipo di abitazione, dove questa è situata, ed anche all’interno della stessa, ad esempio tra una taverna collocata in un seminterrato ed una camera situata al terzo piano o in un sottotetto.

————————————————————

The movements of the wood are largely due to the moisture contained in it. The discussion would be extremely vast but in this post I would like to talk briefly about some aspects linked to the subject, at least those that have the greatest implications with woodworking by hand. For further details, I refer you to the link above.

Unlike materials such as plastic or metal, which are characterized by a homogeneous structure, wood has a marked heterogeneity. Not only between different species but also within the species and the tree itself. This extreme differentiation makes the work of the woodworker even more difficult, since he will not be able to refine himself to a generic knowledge of the wood but must, once the table is placed on the bench and before starting work, carefully evaluate many factors such as the shape, the grain, direction, knots, hardness, moisture, etc. In fact, a whole series of external elements influence, in a more or less decisive way, its heterogeneity, such as the origin of tree, exposure to light and atmospheric agents, climatic and environmental variations,the cutting technique and the sawing, the seasoning method etc.The extreme variability of wood is reflected in continuous movements and extreme instability. It is not difficult to notice how wood has continuous interactions with the primordial elements of nature: fire (in the form of light and heat), air and water. It is also easy to observe this relationship between these elements and the trees. What is less evident, however, is being able to verify how much this interaction continues even after the tree has been felled and even in the finished work. How many times has it happened to see cracks in the top of a table or a piece of furniture or movements of a leg or the loose joints of the drawers that no longer close properly. Well, all these effects are due to the same cause: the loss of wood moisture. Plants, like the human body, are composed of a large percentage of water and this water is lost more or less naturally. In a previous post in this series it was said that, as soon as the tree was felled, water came out of the cut from the outer layers spontaneously and this in turn recalls other water coming from the innermost areas of the plant. This process occurs naturally and without substantial shrinking of the wood (causing only a loss of weight) and stops when the moisture reaches the so-called “saturation point” of the fibers. From this moment on, the wood may lose more moisture through air drying and then through the practice of kiln drying. It is only in these last two phases that the wood begins to retreat and to deform itself, denoting those defects of the cupping, bowing, shrinking and cracking that we will discuss in this post.

The moisture range from the fiber saturation point to zero moisture is called the hygroscopic field. In this period of time the wood interacts continuously with the air giving rise to the phenomena of adsorption (the wood absorbs moisture from the surrounding air) and desorption (the wood releases water in the air in the form of water vapor). In theory, if the two phenomena went hand in hand, the wood would not undergo any change. In reality they differ considerably from each other so that in the wood we can notice swelling due to the absorption of water and cracks, shrinkage and cupping due to the desorption of the same. If we want to summarize the various stages of the descent of moisture in a drying wood, we could say that the newly felled wood has a moisture percentage of about 60%. This moisture decreases naturally after cutting up to values ranging from 28% to 40% (fiber saturation point, conventionally set at 30%). To let the moisture descend again we intervene with the maturing processes. At first with natural seasoning air drying is possible to fall to a moisture of about 22% (to this percentage the wood is called “fresh”) and then it decreases again, up to about 16%. The following is an artificial kiln drying process that can bring humidity up to 0%.

The moisture content of the wood is expressed as a percentage ratio between the weight of the water contained in the wood and the weight of the anhydrous wood (ie without water). There are mainly two measurement methods: gravimetric and electrical. The gravimetric method is the classic method which involves a double weighing: we weigh a fragment of non-seasoned wood, then it is dried in an oven and then re-weighed again. The weight of the dry piece is then subtracted from that of the wet piece, divided by the weight of the dry piece and multiplied by one hundred. Nowadays this method has been largely replaced by the electric one, more convenient and faster, practiced by using specific hygrometers for wood with resistance or dialectical operation.

If we tried to work a timber that had not yet settled with the surrounding humidity, we would obtain boards of shapes different from those desired. The phenomenon of shrinkage, as well as that of expansion and swelling, is not homogeneous on all the wood, varying considerably depending on whether we consider the radial, tangential or axial direction. Furthermore, the shrinkage or dilatation of the wood differs considerably also depending on whether it is a case of softwoods or hardwoods. The phenomenon of shrinkage and swelling is however more noticeable in solid wood compared to other types of wood. The movements in the longitudinal (or axial) direction of the wood are very small. The movement of the wood is instead particularly accentuated in the tangential and radial direction. The movements of the wood, due to the loss of moisture, cause the shrinking of the wood and consequently not only the variation of the dimensions of the table but also of the shape itself. To give an idea of the extent of the phenomenon, a furniture made of solid cherry with a top of about 90 cm. of length placed in a laboratory with 75% humidity, once transferred to a house with 50% humidity it will shrink by about 1 cm.

Before reviewing the various types of changes in the shape of wood, it is interesting to consider a simple but essential rule. Looking at the end grain you will be able to see the growth rings. The wooden rings open as the wood dries to suit their natural tendency to straighten up. From this rule it follows that a table with a tangential cut will tend to deform more than a table with a radial cut. In particular, a sectioned table with a tangential cut will undergo a mainly longitudinal shrinkage, due to the greater traction force of the rings, while a section cut with a radial cut will undergo little shrinkage in the sense of width and almost zero in the sense of thickness. It is generally observed that the outer rings, longer, shrink more than the inner rings. It is for this reason that the boards tend to bend transversely or to cup in the direction of their width, especially in sawn boards with tangential cut.

By cupping or bowing in common language we mean any deformation of the wooden board. In this phenomenon, the cup and bow itself can be included, the warping and the shrinking. In the phenomenon of the cup it is customary to distinguish between transversal shrinking, in which the board curves backwards in the direction of the width and bow, in which the board curves in an arc along its length. In turn, in the longitudinal shrinking, a distinction is made between crook and arching, depending on whether the reaction wood is present on the edge of the table or in the central area of the table. In the phenomenon of twisting it is possible to distinguish between a simple twist, in which the board remains flat but tends to curve at the edges and the concave twisting in which the board appears twisted and with a characteristic helical shape. Finally we have the phenomenon of shrinkage, so that a material with a square section takes on a rectangular shape and a material with a round section takes on an oval shape (commonly it is said that it tends to “diamond”).

In the presence of all these defects water vapor is sometimes used to give moisture to the wood and thus try to “stretch” the fibers, giving them an acceptable shape that will then be further corrected, if not too compromised, with suitable hand tools. A too sudden loss of moisture, besides being the cause of the aforementioned problems, can also generate internal and superficial splits and cracks. Internal cracks are created when the external wood of the table dries faster than the internal one. Superficial cracks generally appear along the medullary rays and are caused by a too fast drying of the wood surface. Finally, the cracks generally originate near the end grain of the wood where the shrinkage phenomenon is greater.

What has been said so far has particular implications for the woodworker. The environment where the work is carried out should have characteristics of brightness and low humidity in relation to the external environment, be fresh and sufficiently ventilated. These particular conditions create an adequate microclimate to limit the movements of the wood due to acclimatization with the surrounding environment and at the same time guarantee a certain degree of healthiness. Not infrequently it can happen instead, especially among the hobbyists, that the woodworking is carried out in basements and garages with too much humidity, little light and very little aeration thus creating a non-optimal climatic situation.

Once transported from the sawmill to the laboratory some practical measures are necessary for the correct acclimatization of the wood. In the first place, direct contact between the same and the external walls, the walls where the water pipes pass and the floors should be avoided as all possible sources of moisture. Secondly, the wood should be arranged horizontally and arranged with the interlayer of spacers that allow both the recirculation of the air between one table and the other that their maintenance in plan. These simple indications will allow to minimize the movements of the wood and facilitate the achievement of a balanced moisture with the environment in which it is located (which in any case will require a period of time varying from a few weeks to a few months).

In the subsequent processing phase, the woodworker will have to cut the pieces, always having the foresight not to ever cut the material to the final size but to always leave margins, (as often happens for example in the practice of the joints) so as to allow the wood to shrink or expand in the joints and according to the place where the final furniture will be placed. If he has to glue boards, the woodworker will have to determine if the final stability of the furniture or its external beauty is more important. If stability is a priority requirement then it will have to proceed to the alternate arrangement of the boards with the growth rings placed in the opposite direction or with the grain of the side-by-side tables that are arranged perpendicularly so that the movements of the wood contrast with each other. If the aesthetic aspect is more important then it will have to rethink the juxtaposition of the tables so as to place them with growth rings all in the same direction and possibly constraining them in a structure that contains the shrinking.

Another factor to take into consideration in the realization of any work is to know the final destination of the work so as to be able to take into account the degree of humidity of the environment where it will be placed and consequently choose the most suitable type of timber. There are no significant differences in humidity only between indoor and outdoor environments but also depending on the type of house, where it is located, and also inside it, for example between a tavern located in a basement and a room located on the third floor or in an attic.

Lascia un commento