Il legno e la sua lavorazione manuale. Patologie e malformazioni della pianta. / Wood And woodworking by hand. Pathologies and malformations of the plant.

English translation at the end of the article

Un falegname, qualsiasi opera intenda realizzare, dovrà innanzitutto scegliere dove reperire la materia prima, ovvero il legname. Affronteremo questo argomento nello specifico in seguito. Per il momento basti dire che, ove possibile, sarebbe opportuno orientarsi sulle segherie, in particolare quelle nelle quali sia presente una vasta

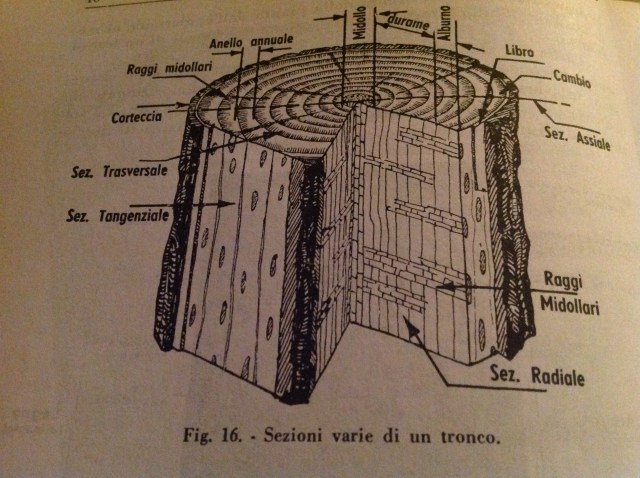

scelta di legname, meglio se di prima qualità. Chi più spende meno spende e questo vale anche nella lavorazione del legno. Scopriremo infatti che la scelta del legname è determinante per la buona riuscita del manufatto. In commercio esistono tavole di prima, seconda e terza scelta (o qualità) ma, alla luce di quanto appena detto, la decisione dovrebbe ricadere su legname di prima qualità, lasciando il resto per realizzazioni di minor pregio e senza particolari pretese. Detto questo l’artigiano, recatosi in segheria, dovrà verificare in primo luogo la qualità delle tavole facendo affidamento sulle proprie conoscenze e sulla propria esperienza. La selezione della giusta tavola è una procedura che investe quasi tutti i sensi di cui siamo provvisti. Vista, tatto e olfatto sono indispensabili nella prima fase di scelta delle tavole, ma anche l’udito sarà determinante, soprattutto durante la seconda fase, quella della lavorazione manuale. La prima cosa che deve attrarre l’attenzione dell’artigiano è comunque l’aspetto complessivo esteriore della tavola. Molto spesso gli alberi sono soggetti a malformazioni e patologie che si ripercuotono inevitabilmente sulla qualità finale del legname. Talune di queste malformazioni e patologie sono visibili ad occhio nudo come i nodi, le sacche di resina, gli imbarcamenti e le fessurazioni. Molte altre non sono rilevabili, né osservando la tavola esteriormente né tantomeno osservando esternamente l’albero, in quanto si manifestano soltanto nella fase di segagione. Le malformazioni congenite sono quelle che si rivelano durante la vita della pianta. Non sono dovute a particolari cause esterne ma sono vere e proprie anomalie legate alla sua crescita. Anche le patologie sono malattie che colpiscono la pianta durante la sua vita ma si originano a seguito di eventi esterni, siano essi di origine naturale, climatica, vegetale, animale o umana. Analizziamo di seguito le principali di queste malformazioni congenite e le patologie che affliggono la pianta, penalizzando sensibilmente la qualità del legname.

Nodi vivi o fissi.

Questa malformazione si forma quando l’albero, aumentando di diametro, ingloba la base di un ramo vivo che diventa così parte del tronco stesso. Nell’albero in vita il nodo rappresenta la sede da dove si originano i nuovi rami. Quando l’albero viene tagliato esso viene allo stesso tempo privato anche dei rami e le loro sedi vengono ricomprese nel tronco.

I nodi assumono un colore leggermente più scuro, si presentano con forma pressoché sferica e sono di consistenza più dura rispetto al legno circostante. La presenza del nodo è facilmente riconoscibile anche per il particolare disegno che le venature del legno creano attorno ad esso. Osservando una tavola infatti le fibre, che solitamente viaggiano parallele, in presenza del nodo si dipartono abbracciandone la forma per poi ricongiungersi una volta “aggirato l’ostacolo”.I nodi vivi o fissi, che si originano dai rami giovani degli alberi, creano diverse problematiche se presenti in una tavola da lavorare. Il nodo, di per sé, essendo di maggior durezza, risulta di difficile lavorazione, è ostico da piallare, da spianare e da segare ed è a rischio fenditura e distacco. Generalmente le fibre, in presenza del nodo, creano delle sorte di pinnacoli, ovvero delle zone più alte rispetto al legno circostante, che ne rendono talvolta impraticabile la lavorazione con i normali utensili manuali. Può accadere però che, proprio a causa di questa imperfezione, siano comunque ricercate, per la particolare bellezza che le venature assumono attorno al nodo, ulteriormente magnificabile in fase di finitura del manufatto. La maggiore o minore presenza di nodi dipende essenzialmente dalla tipologia di legno, differenziandosi così da essenza ad essenza. Dei nodi vivi viene proposta una classificazione abbastanza eterogenea a seconda della forma e della posizione che assumono nel legname. Si distingueranno così nodi passanti, a grappolo, di spigolo ecc. Nel segato di bassa qualità si può notare frequentemente anche la presenza dei nodi morti o mobili.

Nodi morti o mobili.

A differenza dei nodi vivi o fissi che si generano dalla segagione di un ramo vivo della pianta, i nodi morti o mobili si generano dal taglio di un ramo già secco. Il ramo può seccarsi per cause naturali, per stroncatura o per taglio che, nelle latifoglie, se non viene fatto aderente alla corteccia, con il passare del tempo può essere ricoperto dalla pianta in accrescimento e, non essendo più alimentato, destinato a marcire. Nelle conifere invece, per effetto della resina presente nel legno, il ramo non marcisce ma rimane estraneo al tronco. Questo fenomeno può dar luogo, una volta ridotto il tronco in tavole, alla fuoriuscita del nodo stesso lasciando il classico foro nel legno. Il nodo morto presenta un colore molto più scuro del legno circostante e in fase di essiccazione si comporta in modo diverso, contraendosi di fatto in misura maggiore, e dando luogo, anche in questo caso, al suo distacco. Come detto la presenza di nodi morti denota una tavola di scarsa qualità e pessima tenuta, oltre alla difficile lavorabilità. È facile immaginare quanto sia antiestetico un mobile realizzato con legno bucato! Un tempo si usava riempire il foro lasciato nel legno dalla caduta del nodo morto con dei cilindri di ugual misura e dello stesso materiale. Oggigiorno si preferisce evitare il problema selezionando tavole prive di nodi morti anche se spesso sono reperibili, specie nei bricocenter, tavole di terza fascia economiche con una consistente presenza di questa imperfezione.

La quantità dei nodi presenti in una tavola di legno dipende dal tipo di albero dal quale la tavola è stata ricavata. L’Abete, tanto per citare un’essenza comunemente usata in Italia, risulta essere un legno particolarmente nodoso. Questa caratteristica, legata alla facile reperibilità, ne determina il prezzo particolarmente conveniente e ne fa un legno dagli svariati utilizzi e ricercato soprattutto dagli hobbisti. La malformazione congenita dei nodi risulta ben visibile ad occhio nudo. Purtroppo molte malformazioni non sono altrettanto visibili e si scoprono solo a taglio del tronco avvenuto. Di seguito le più importanti.

Le fessurazioni.

Le fessurazioni sono spaccature dovute al gelo o al ritiro stagionale del legno. Tali fessurazioni possono essere presenti sia longitudinalmente sia in testa alla tavola ed allargandosi provocano danni spesso irrimediabili alla struttura del legno. Un’errata essiccazione o una troppo forte esposizione al gelo possono causare questa imperfezione, ma anche l’imperizia nel trasporto delle tavole e il loro errato stoccaggio possono esserne la causa.

Le sacche di resina.

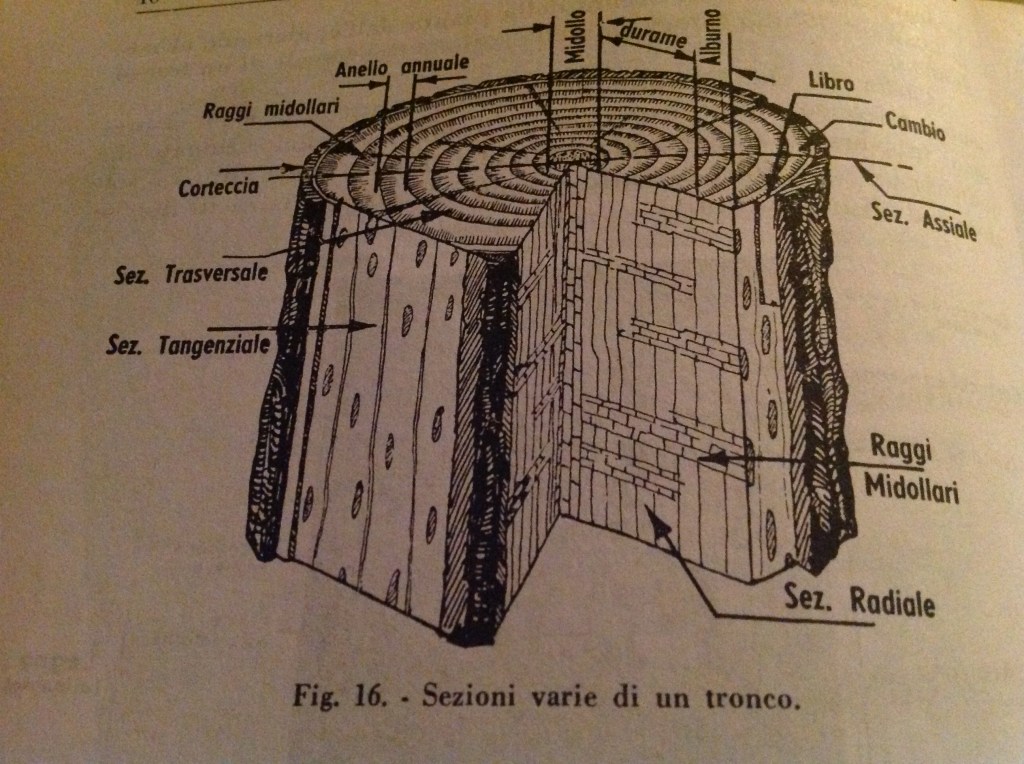

Sono molto comuni nelle conifere. Trattasi di cavità negli anelli del legno originatesi dall’improvvisa interruzione dei canali che trasportano la resina e che danno luogo alla continua fuoriuscita di questa sostanza anche in manufatti già lavorati. Le sacche di resina possono essere provocate anche da lesioni accidentali dell’albero.

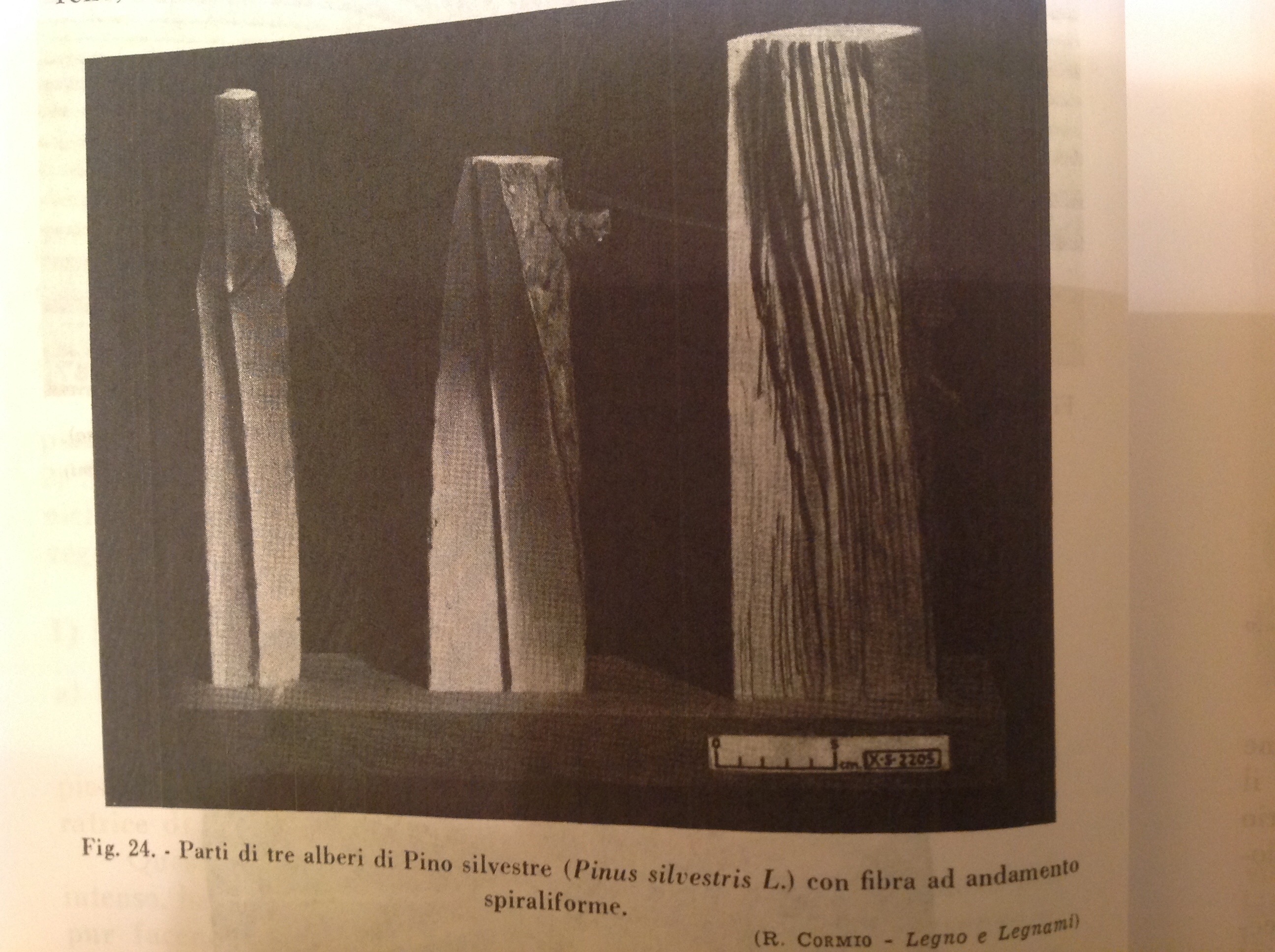

Le fibre irregolari.

Le fibre irregolari risultano visibili solo a segagione avvenuta. In questo caso le fibre non corrono in modo parallelo all’asse del tronco ma si contorcono, avviluppandosi su se stesse in forme spiraliformi o elicoidali, talvolta molto evidenti. Le cause di tale anomalia non sono del tutto chiare ma ne sembra comunque accertata la sua ereditarietà. Talvolta le condizioni climatiche come il vento e la tipologia di terreno, oltre che la vecchiaia dell’albero stesso ne determinano la malformazione. Inutile dire che tale legno, essendo di difficile lavorazione per l’estrema irregolarità delle fibre, non è ricercato ed è di scarsissimo valore commerciale.

Il cuore multiplo.

Il cuore multiplo è un’altra patologia che non è visibile ad occhio nudo ma solo a taglio del tronco avvenuto.

Questa malformazione si manifesta quando due o più germogli, o getti, si sono sviluppati dallo stesso seme e con la crescita sono rimasti conglobati in una sola corteccia, creando un unico albero. Si chiama cuore multiplo perché osservando il tronco segato orizzontalmente si osservano due o più cuori in base al numero di germogli che con il tempo si sono fusi in un’unica pianta. Il cuore multiplo viene denominato anche doppio midollo, anche se in realtà quest’ultimo si genera in modo diverso, ovvero quando due piante, inizialmente separate ma molto vicine, si uniscono dando origine ad un tronco unico continuando tuttavia quest’ultimo a preservare, al suo interno, un doppio midollo. Tale fenomeno è conosciuto anche con il nome di concrescimento. La differenza tra cuore multiplo e doppio midollo può quindi rilevarsi nel momento in cui si genera la malformazione: alla nascita, dal germoglio, nel caso del cuore multiplo e durante la crescita per unione di due piante nel caso del doppio midollo. Anche in questo caso così come detto per le fibre irregolari, il legno che presenta tale malformazione è di difficile lavorazione, incontrando nella stessa tavola diverse venature contrastanti e di andatura irregolare. La piallatura non risulterà scorrevole e spesso si incorrerà nello strappo delle fibre, inconveniente che si verifica quando si lavora il legno non seguendo correttamente l’ andamento della venatura o addirittura lavorandolo contro vena (c.d. tear out). Così come tutti i legni che presentano malformazioni congenite che ne rendono difficile la lavorazione anche questo tipo di legno è di scarso valore commerciale e scarsa ne è la tenuta.

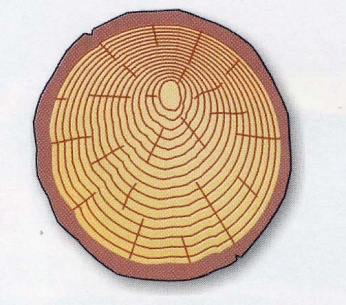

Il cuore spostato.

Sempre parlando del cuore del legno un’altra malformazione è la presenza del cuore spostato. Sezionando il tronco trasversalmente infatti è osservabile il cuore in posizione non centrale ma spostato verso l’esterno. Questo difetto è dovuto essenzialmente al luogo ed alle condizioni climatiche dove l’albero è cresciuto. Se l’albero si è sviluppato su un terreno scosceso presenterà il cuore spostato verso la montagna, così come se l’albero è cresciuto vicino ad un muro o ad un qualsivoglia ostacolo, presenterà il cuore spostato dalla parte dove l’albero poteva essere raggiunto dai raggi solari. Tale difetto è riscontrabile anche in quelle piante che non hanno potuto sviluppare in modo armonioso le proprie radici a causa di un impedimento (cemento, rocce, ecc.). Lo sviluppo degli anelli, nelle piante affette da questo tipo di problematica, risulterà non omogeneo. Questi evidenzieranno infatti una maggior ampiezza da un lato e risulteranno più stretti dall’altro, mostrando la caratteristica andatura ellittica. Il tavolame ricavato da questo tipo di legno, presentando un andamento della venatura irregolare, risulterà di difficile lavorazione.

Doppio alburno o lunatura.

Gli alberi, come qualsiasi organismo vivente, sono particolarmente sensibili al clima dove vivono.

Condizioni climatiche estreme come il troppo caldo, il troppo freddo, l’azione del vento e della pioggia possono talvolta interferire sul normale sviluppo causando alterazioni visibili sul tronco stesso o in una fase successiva, a segagione avvenuta. Quando le temperature sono troppo basse le piante gelano e si può generare l’alterazione del doppio alburno o lunatura. Il doppio alburno o lunatura viene determinato dalla morte delle cellule dell’alburno in seguito alle basse temperature. Questa zona priva di vita viene in seguito racchiusa dagli anelli esterni che non hanno risentito dell’azione del freddo e che hanno creato a loro volta un secondo alburno. Generandosi nello stesso tronco due alburni il legno perde di omogeneità e risulta difficilmente lavorabile.

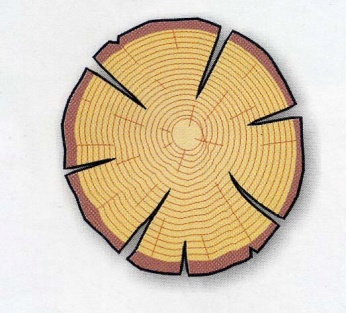

La cipollatura.

Il troppo caldo, il troppo freddo e il vento intenso possono provocare anche l’alterazione detta cipollatura. La cipollatura consiste nel distacco degli anelli della pianta che può essere totale o parziale. Il distacco parziale è meno grave, quello totale è più grave e provoca la creazione nello stesso tronco di due fusti, uno cilindrico interno e uno cavo esterno. Difficilmente è possibile accorgersi esternamente della presenza di tale difetto. Talvolta però, se il distacco si è verificato negli anelli più esterni, è possibile accertarne la presenza prima del taglio del tronco operando la pratica del martellamento della corteccia. Se otteniamo un suono cupo allora è probabile che all’interno si siano verificati dei distacchi.

Aggressioni da parassiti animali, vegetali e dall’uomo.

Le aggressioni che subisce un albero provengono spesso dallo stesso mondo naturale al quale esso stesso appartiene. Abbiamo già parlato dell’influenza, talvolta negativa, che può avere il clima nelle sue forme estreme di troppo caldo, troppo freddo, vento, piogge intense ecc. Talvolta l’albero viene attaccato dai funghi, che sono parassiti vegetali del legno. I funghi possono essere già presenti nell’albero in vita ma anche attaccare il tavolame già tagliato e messo a dimora. Sono dannose alla pianta anche tutte le specie vegetali che talvolta ricoprono il fusto dell’albero come l’edera, i muschi, i licheni ed il vischio. Oltre alle aggressioni vegetali, l’albero, ma soprattutto il tavolame già segato ed i mobili, possono essere oggetto di attacchi da parte di animali parassiti del legno. Molto spesso trattasi di piccolissimi insetti, come gli xilofagi (comunemente conosciuti come tarli del legno) che, scavando lunghi cunicoli nelle vecchie masserizie e nelle vecchie travi (specialmente quando non trattate), ne diminuiscono la stabilità. In commercio esistono sostanze chimiche che combattono questi parassiti (come ad esempio la Permetrina) e rimedi pratici come lo stucco di legno con il quale è possibile chiudere gli antiestetici forellini tipici del legno tarlato. Il sistema comunemente usato consiste nell’applicazione sulla superficie da trattare della sostanza antitarlo tramite spennellatura e/o siringatura all’interno dei cunicoli ed alla successiva messa a dimora in luogo buio (meglio se dentro ad un sacco nero ben chiuso in modo da privare i tarli dell’ossigeno necessario). Potrebbe rivelarsi opportuno ripetere l’operazione più volte prima di poter ottenere il risultato desiderato. Molto spesso il legno tarlato è sinonimo di mobile antico ma occorre diffidare di taluni antiquari che cercano di “invecchiare” il mobile ad arte praticando dei forellini nel legno simulandone così la loro presenza. Il tarlo appartiene alla famiglia dei coleotteri ma non è l’unico insetto che si nutre di legno. Anche le termiti, anch’esse xilofagi appartenenti alla famiglia degli isotteri, si nutrono della cellulosa presente nel legno ed attaccano spesso i mobili più vecchi. La loro opera di distruzione è invisibile, a differenza del tarlo che lascia un piccolo cumulo di polvere alla base del legno. Nelle zone marine temperate e tropicali anche altri tipi di insetti come le teredini distruggono il legname. Il tarlo e le termiti sono i più conosciuti parassiti animali del legno ma in natura ne esistono molti altri, meno noti ma ugualmente dannosi alla sua stabilità. Anche l’uomo con la sua azione può causare danni agli alberi. Non è il caso di trattare in questa sede il rapporto conflittuale tra uomo e natura. Per quello che riguarda l’argomento in questione basti ricordare l’imperizia di talune operazioni effettuate dall’uomo sulle piante come ad esempio errate o troppo frequenti potature che creano eccesso di nodi nel legno o la scortecciatura della pianta che può dar luogo, nella parte che non si rigenera autonomamente, a rigonfiamenti, marciume e attacchi di insetti.

Cuore rosso.

Il cuore rosso è una grave alterazione che ha luogo nella parte centrale del tronco. È riconoscibile dal colore più intenso che assume il cuore rispetto al resto della pianta (da qui la derivazione del suo nome). Cause di tale patologia possono essere un terreno non adatto, i parassiti, potature non effettuate correttamente, gli agenti atmosferici e la vecchiaia dell’albero stesso.

Stellatura.

Le stellature sono provocate da tensioni interne al legno e si verificano lungo i raggi del tronco, dove il tessuto risulta più debole. Trattasi di ampie e profonde spaccature che, solcando radialmente il tronco, ne pregiudicano la stabilità.

Carie del legno.

La carie del legno si origina a causa dell’attacco di spore, conidi e frammenti di micelio, praticamente dei funghi che, penetrando all’interno del legno attraverso potature, insetti e ferite naturali, ne provocano lo strutturale indebolimento. Le principali tipologie di carie del legno sono la carie bianca e la carie bruna.

In questo post ho cercato di offrire una veloce panoramica delle principali malformazioni e patologie che possono affliggere il legno. Con queste e con molte altre il falegname ha continuamente a che fare, principalmente quando si trova nella prima fase della lavorazione manuale ovvero quella della scelta del legname che, assieme alla progettazione, segnano per l’appunto l’inizio di qualsiasi lavorazione amanuense. Molte patologie, come detto, non sono visibili ad occhio nudo ma si rivelano soltanto nella fase di taglio del tronco. Fortunatamente le tavole che si trovano in commercio sono molto spesso esenti dalla maggior parte delle patologie indicate sopra. I difetti che effettivamente si riscontrano nelle tavole vendute nelle segherie e nei grandi magazzini del fai da te presentano quasi sempre le solite, note, imperfezioni come ad esempio i nodi (sia vivi che morti), le sacche di resina, le fessurazioni e poco altro. Sovente invece molte di queste tavole sono affette da difetti di altra natura, non dovuti cioè a vere e proprie patologie della pianta ma ad errati procedimenti di stagionatura, essiccazione, trasporto e stoccaggio e dai quali derivano altri tipi di problematiche (come ad esempio il fenomeno dell’imbarcamento), che l’artigiano si troverà ad affrontare nella successiva fase di lavorazione. In conclusione si può già intravedere la complessità della lavorazione manuale del legno. Fondamentale in queste fasi è l’esperienza e la perizia nel saper scegliere il legname per non trovarsi in difficoltà nel prosieguo del lavoro. Taluni difetti non lasciano alcuna possibilità di intervento, altri possono essere corretti usando gli strumenti opportuni. Per questo motivo la messa a punto degli utensili manuali deve essere effettuata con il massimo scrupolo possibilmente alla fine di ogni giornata lavorativa, così da renderli già efficienti per il giorno successivo. Nei prossimi post di questa serie vedremo dapprima le proprietà tecnologiche, fisiche e meccaniche dei legnami per poi passare in rassegna successivamente i principali sistemi di stagionatura, essiccazione e conservazione partendo dalla fase dell’abbattimento della pianta. Questo ci servirà per comprendere come debba comportarsi l’artigiano nella lavorazione del legno, tenendo conto di fattori come la fendibilità, flessibilità, porosità, umidità, temperatura, ventilazione, esposizione ai raggi solari, ecc.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

A woodworker, in any work intends to achieve, must first choose where to find the timber. We will discuss about that in future articles. For the moment, it is sufficient to say that, where possible, it would be advisable to search in sawmills, in particular those in which there is a wide choice of wood, better if of first quality. Those who spend more spend less and this is also true in woodworking. In fact, we will discover that the choice of wood is decisive for the success of our work. On the market there are boards of first, second and third choice (or quality) but, according to what has just been said, the decision should fall on top quality wood, leaving the rest for less valuable works. So, the woodworker, who went to the sawmill, will first have to check the quality of the boards, relying on his own knowledge and experience. The selection of the right board is a procedure that invests almost all the senses we have. Sight, touch and smell are essential in the first phase of choice of the wood, but also the hearing will be crucial, especially during the second phase, when handworking. The first thing that must attract the attention of the woodworker, however, is the overall exterior appearance of the board. Often the trees are subject to malformations and diseases that inevitably affect the final quality of the wood. Some of these malformations and pathologies are visible to the naked eye, such as knots, resin pockets, vessels and cracks. Many others are not detectable, neither by looking at the wood externally nor by looking externally at the tree, as they occur only in the sawing phase. Congenital malformations are those that are revealed during the life of the plant. They are not due to particular external causes but they are real anomalies related to its growth. Diseases are diseases that affect the plant during its life but originate as a result of external events, be they of natural, climatic, plant, animal or human origin. We analyze below the main of these congenital malformations and the diseases that affect the plant, significantly penalizing the quality of the wood.

Live or fixed nodes.

This malformation takes place when the tree, increasing in diameter, incorporates the base of a live branch which thus becomes part of the trunk itself. In the living tree the node represents the seat from where the new branches originate. When the tree is cut it is at the same time also deprived of branches and their seats are included in the trunk.

This kind ok knots are of a slightly darker color, they have an almost spherical shape and are of a harder consistency than the surrounding wood. The presence of the knot is easily recognizable also for the particular design that the grain of the wood create around it. Observing a board in fact the fibers, which usually are parallel, in the presence of the node branch off embracing the shape and then rejoin once “bypassed the obstacle.” The live or fixed nodes, which originate from the young branches of the trees, create different problems if they are present in a board that we have to work by hand. The knot itself, being of greater hardness, is difficult to work with, is difficult to plan, to saw and is at risk of cracking and detachment. Generally the fibers, in the presence of the knot, create some kind of pinnacles, that are higher areas near the surrounding wood, which make it sometimes impractical to work with normal hand tools. However, it may happen that, because of this imperfection, they are in great demand, due to the particular beauty of the grain around the knot, which can be magnified during the finishing phase. The greater or less presence of knots depends essentially on the type of wood, thus differentiating itself from essence to essence. A fairly heterogeneous classification is proposed of the live nodes depending on the shape and position they assume in the wood. In this way, passing nodes, like bunches, edges, etc., will be distinguished. In the low-quality sawn timber, the presence of dead or mobile knots can also be frequently noticed.

Dead or mobile knots.

As the live or fixed nodes are generated by sawing a live branch of the plant, dead or mobile knots are generated by cutting an already dry branch. The branch can dry up due to natural causes, for cropping or for cutting that, in broadleaves, if it is not adherent to the bark, with the passage of time it can be covered by the growing plant and, being no longer fed, destined to rot. In coniferous trees, however, due to the resin present in the wood, the branch does not rot but remains apart from the trunk. This phenomenon can give rise, once the trunk is reduced to boards, to the exit of the node itself, leaving the classic hole in the wood. The dead knot has a much darker color than the surrounding wood and in the process of drying behaves differently, contracting itself to a greater extent, and giving rise, even in this case, to its detachment. As mentioned, the presence of dead knots denotes a board of poor quality and poor sealing, as well as difficult workability. It is easy to imagine how ugly a piece of furniture made of such a wood is! Once to fill the hole left in the wood by the fall of the dead knot were used cylinders of the same size and of the same material. Nowadays it is preferable to avoid the problem by selecting boards without dead knots even if they are often available, especially in the bricocenter, boardd of the third economic band with a substantial presence of this imperfection.

The quantity of nodes present in a wooden board depends on the type of tree from which the board has been obtained. Spruce, to mention an essence commonly used in Italy, turns out to be a particularly gnarled wood. This feature, together with the easy availability, determines the price particularly convenient and makes it a wood of various uses and very requested by hobbyists. The congenital malformation of the nodes is clearly visible to the naked eye. Unfortunately, many malformations

they are not so visible and are discovered only when the trunk is cut. Here are the most important.

Cracks.

Cracks are splits due to frost or seasonal wood shrinkage. These cracks can be present both longitudinally and at the top of the board and when spreading they cause damage often irremediable to the structure of the wood. Incorrect drying or too strong exposure to frost can cause this imperfection, but also the inexperience in transporting boards and their incorrect storage can be the cause.

The resin bags.

They are very common in conifers. These are cavities in the rings of wood originated by the sudden interruption of the channels that transport the resin and which give rise to the continuous release of this substance even in manufactured furniture already worked. Resin bags can also be caused by accidental shaft damage.

The irregular fibers.

The irregular fibers are visible only after sawing. In this case the fibers do not run parallel to the axis of the trunk but are twisted, enveloping themselves in spiral or helical shapes, sometimes very evident. The causes of this anomaly are not completely clear, but its inheritance seems to have been established. Sometimes the climatic conditions like the wind and the type of ground, as well as the old age of the tree itself, determine the malformation. Needless to say, this wood, being difficult to process due to the extreme irregularity of the fibers, is not wanted and is of very low quality.

The multiple heart.

The multiple heart is another pathology that is not visible to the naked eye but only when the trunk is cut.

This malformation occurs when two or more shoots, or jets, have developed from the same seed and with the growth they have remained conglobated in a single bark, creating a single tree. It is called multiple heart because by observing the horizontally truncated trunk two or more hearts are observed according to the number of shoots that have merged with time in a single plant. The multiple heart is also called double marrow, even if in reality the latter is generated in a different way, that is when two plants, initially separated but very close, they come together giving origin to a single trunk but continuing the latter to preserve, inside, a double marrow. This phenomenon is also known by the name of growth. The difference between multiple heart and double marrow can therefore be detected in the moment in which the malformation is generated: at birth, from the shoot, in the case of the multiple heart and during the growth by union of two plants in the case of the double marrow. Also in this case, as mentioned for the irregular fibers, the wood which presents this malformation is difficult to work, meeting in the same board different contrasting and irregular grains. The planing will not be smooth and will often incur the tearing of the fibers, a problem that occurs when working the wood not correctly following the grain pattern or even working against the grain (c.d. tear out). As well as all woods that have congenital malformations that make it difficult to process even this type of wood is of little commercial value and the seal is poor.

The heart moved.

Always speaking of the heart of the wood another malformation is the presence of the moved heart. If the trunk is transversely cut, in fact the heart can be seen in a non central position but moved outwards. This defect is essentially due to the place and the climatic conditions where the tree has grown. If the tree has developed on a steep ground it will present the heart moved towards the mountain, as if the tree has grown near a wall or any obstacle, it will present the heart moved to the side where the tree could be reached from the sun’s rays. This defect is also found in those plants that have not been able to develop their roots harmoniously due to an impediment (cement, rocks, etc.). The development of the rings, in plants affected by this type of problem, will result not homogeneous. These will in fact show a greater width on one side and will be closer to the other, showing the characteristic elliptical gait. The boards obtained from this type of wood, presenting a pattern of irregular grain, will be difficult to work.

Double sapwood or lunature.

Trees, like any living organism, are particularly sensitive to the climate in which they live.

Extreme climatic conditions such as too much heat, too much cold, the action of wind and rain can sometimes interfere with normal development causing visible alterations on the trunk itself or at a later stage, after the sawing has occurred. When the temperatures are too low, the plants freeze and the alteration of the double sapwood or the lunature can be generated. The double sapwood or lunature is determined by the death of the sapwood cells following low temperatures. This area without life is later enclosed by external rings that have not been affected by the action of the cold and which have in turn created a second sapwood. By generating two sapwoods in the same trunk, the wood loses its homogeneity and is difficult to work with.

The ring shake cipollatura.

The overheating, the too cold and the intense wind can also cause the alteration of the so called “cipollatura”. It consists in detaching the rings of the plant which can be total or partial. The partial detachment is less severe, the total detachment is more serious and causes the creation of two cylindrical barrels, one internal cylindrical and one external barrel in the same trunk. It is difficult to notice externally the presence of this defect. Sometimes, however, if the detachment has occurred in the outermost rings, it is possible to notice its presence before cutting the trunk by operating the hammering of the bark. If we get a gloomy sound then it is probable that detachment has occurred inside.

Aggressions from animal, plant and human parasites.

The aggressions that a tree undergoes often come from the same natural world to which it belongs. We have already talked about the influence, sometimes negative, that can have the climate in its extreme forms of too hot, too cold, wind, heavy rains, etc. Sometimes the tree is attacked by fungus, which are plant parasites of the wood. Fungus may already be present in the tree during life but also attack the already cut and put away board. All plant species that sometimes cover the stem of the tree such as ivy, moss, lichens and mistletoe are also dangerous to the plant. In addition to plant aggressions, the tree, but above all the sawn timber and furniture,they can be attacked by wood parasitic animals. Very often they are very small insects, such as xylophages (commonly known as woodworms) that, by digging long tunnels in old furnitures and in the old beams (especially when not treated), reduce their stability. On the market there are chemical substances that fight these parasites (such as the Permethrin) and practical remedies such as wood putty with which you can close the unsightly little holes typical of worm-eaten wood. The commonly used system consists in the application on the surface to be treated of the woodworm substance by brushing and / or syringing inside the tunnels and the subsequent placing in a dark place (better if inside a well closed black bag in order to deprive the woodworks of the necessary oxygen). It may be advisable to repeat the operation several times before the desired result can be achieved. Very often the worm-eaten wood is synonymous with antique furniture but it is necessary to be aware of some antique dealers who try to “age” the piece of furniture by practicing small holes in the wood, thus simulating their presence. The worm belongs to the family of the beetles but it is not the only insect that feeds on wood. Even the termites, also xylophagi belonging to the family of the isotteri, feed on the cellulose present in the wood and often attack the older furniture. Their work of destruction is invisible, unlike the woodworm that leaves a small pile of dust at the base of the wood. In the temperate and tropical marine areas also other types of insects such as the teredini destroy the timber. The woodworms and termites are the best known animal pests of wood but in nature there are many others, less known but equally dangerous to its stability. Even man with his action can cause damage to trees. It is not the case to treat here the conflictual relationship between man and nature. With regard to the subject in question suffice to recall the inexperience of certain operations carried out by man on plants such as erroneous or too frequent pruning that create excess knots in the wood or the debarking of the plant that may give rise, in the part that does not regenerate itself independently, swelling, rot and insect attacks.

Red heart.

The red heart is a serious alteration that takes place in the central part of the trunk. It is recognizable by the more intense color that the heart takes with respect to the rest of the plant (hence the derivation of its name). Causes of this pathology may be unsuitable soil, parasites, pruning not done correctly, atmospheric agents and old age of the tree itself.

Spangle.

The spangle is caused by tensions inside the wood and occur along the rays of the trunk, where the fabric is weaker. These are large and deep splits that, radiating the trunk radially, affect its stability.

Wood caries.

The wood caries originates due to the attack of spores, conidia and fragments of mycelium, practically fungus that, penetrating the wood through prunings, insects and natural wounds, cause its structural weakening. The main types of wood caries are white caries and brown caries.

In this post I tried to offer a quick overview of the main malformations and diseases that can afflict the wood. With these and many others, the woodworker has continually to do, mainly when he is in the first phase of woodworking or in the choice of wood that, together with the project, mark the beginning of any handworks. Many diseases, as mentioned, are not visible to the naked eye but are revealed only during the cutting of the trunk. Fortunately, the boardd that are on the market are very often free of most of the diseases mentioned above. The defects that are actually found in the tables sold in sawmills and department stores of do-it-yourself almost always present the usual, known, imperfections such as knots (both alive and dead), resin bags, cracks and little else . Often, however, many of these boards are affected by defects of other nature, not due to real plant diseases but to incorrect processes of curing, drying, transport and storage and from which derive other types of problems (such as the phenomenon of cup, twist, bow ), which the woodworker will face in the subsequent processing phase. In conclusion, it is clear the complexity of woodworking by hand. Fundamental in these phases is the experience and expertise in knowing how to choose the wood so as not to be in difficulty in the continuation of the work. Some faults leave no possibility of intervention, others can be corrected using the right tools. For this reason, the setting up of hand tools must be carried out with the utmost care, possibly at the end of each working day, so as to make them already efficient for the next day. In the next posts of this series we will first see the technological, physical and mechanical properties of the wood and then review the main systems of curing, drying and storage starting from the phase of slaughter of the plant. This will help us to understand how the craftsman should behave in wood processing, taking into account factors such as feasibility, flexibility, porosity, humidity, temperature, ventilation, exposure to sunlight, etc.

Alcune foto ed immagini sono state tratte da siti internet esterni per soli scopi informativo didattici e senza fini di lucro. Se si è proprietari delle immagini e se ne desidera la rimozione si prega di segnalarlo nella sezione contatti.

Lascia un commento